L.I. How Did We Get Here? Land Use and Housing

Land Use and Housing

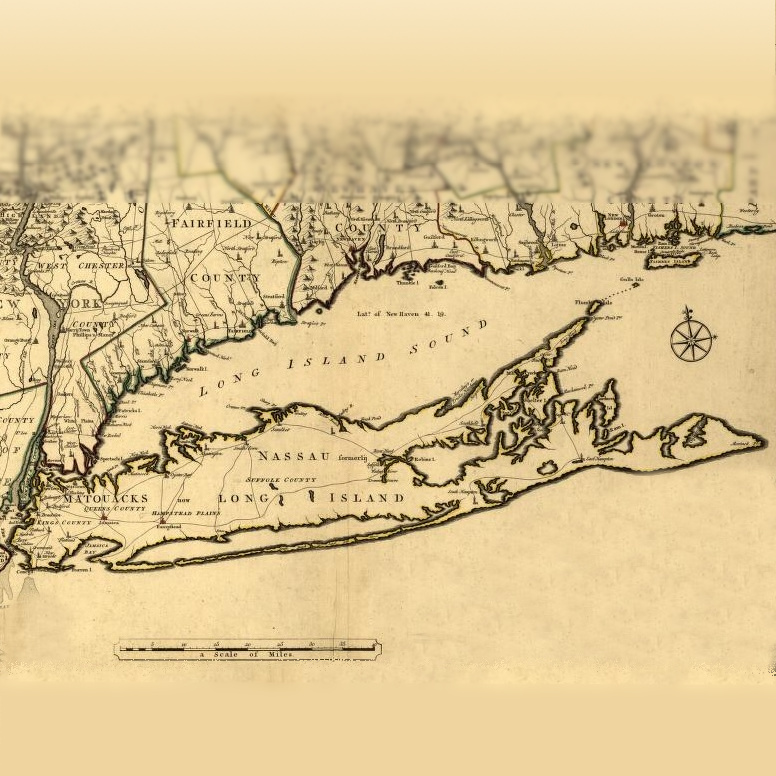

A Timeline of Land Use and Housing on Long Island

Post-World War II, the modern suburbs were born on Long Island. World-class parks and beaches, outstanding schools, proximity to New York City, and the opportunity for home ownership in safe communities like the newly constructed Levittown all seemed to come together to fulfill the national ethos of the American Dream. However, land use decisions made by local governments also created a very high reliance upon the automobile and a legacy of segregated communities.

As Long Islanders learn from our shared history, new approaches to land use decision-making are taking hold. Over time, fewer single-family home subdivisions are being proposed, and instead, the focus has shifted to revitalizing downtowns with transit-oriented developments and with stakeholder collaborative planning. Now, more communities across Long Island are rejecting the top-down model and instead working to engage civic leaders early in the planning process to create walkable communities, with multi-family mixed-use buildings in downtowns, near train stations, and with a mix of housing types, including, in some cases, a percentage of more affordable, workforce housing set-asides. In many parts of the birthplace of both suburbia and suburban sprawl, there is now an embrace of smart growth planning principles.

In order to bring communities together to address today’s housing and land use challenges, it can be instructive to first consider our shared history and ask the question, Long Island: How Did We Get Here?

This 14-minute video covers major milestones from the timeline of events and trends that led to suburban sprawl dominating the landscape of Long Island in the mid-to-late 20th century, and the reactions against it, first through open space conservation efforts and more recently growing acceptance of smart growth principles.

LAND USE AND HOUSING ON LONG ISLAND — TIMELINE OF EVENTS

1867–1879 Minimum Housing Standards developed in New York City

In 1864, the Council of Hygiene and Public Health was organized to improve sanitary conditions in New York City. Under its leadership, the Metropolitan Board of Health was established in 1866, and a year later, in 1867, the first tenement house law was enacted to define the minimum standards of housing in the city. At the time there were 15,000 tenement houses in the city, all of which had been built without any legal regulations whatsoever. The law provided some remedies to existing houses but did not secure any type of new construction.

More Details +

In 1864, the Council of Hygiene and Public Health was organized to improve sanitary conditions in New York City. Under its leadership, the Metropolitan Board of Health was established in 1866, and a year later, in 1867, the first tenement house law was enacted to define the minimum standards of housing in the city. At the time there were 15,000 tenement houses in the city, all of which had been built without any legal regulations whatsoever. The law provided some remedies to existing houses but did not secure any type of new construction.

Very little attention was given to this issue from the establishment of the tenement house law until 1877, when Alfred Tredway White of Brooklyn endeavored to benefit working people of the city with decent and comfortable housing. White built his “Home Buildings” in Brooklyn, and a year later had constructed an entire block of model tenements with a large park or courtyard in the center, which validated that decent housing was valued and could be profitable.

With wide publicity given to White’s experiment, a mayor’s committee was selected to develop ways for tenement house reforms to be established. Capital was raised for better-quality dwellings in old New York that followed White's Brooklyn model, and a new tenement house law was enacted in 1879.

1894 — Home Rule

The struggle for increased home rule powers for cities in New York had been protracted and challenging. It was not until the late 1800s that the State Legislature began applying statutes to cities generally rather than passing specific laws on individual local issues. Municipal Home Rule was a major issue at the New York Constitutional Convention of 1894. As a result of its recommendations, cities were divided into three classes based on population size to facilitate the Legislature in passing general laws that addressed the problems of cities of different sizes. Home rule was later expanded to all towns and villages, putting the power of zoning in the hands of the most local units of government, towns, cities, and villages.

NYS Senator Charles L. Guy opinion piece, 1894.

1916 — Zoning Emerges

As the discussion of protecting property values through zoning restrictions was emerging nationally, New York City’s Building Zone Resolution was adopted on July 25, 1916. It marked the first citywide zoning law in the United States and had a major impact on urban planning in both the United States and internationally. The principal authors of the resolution were George McAneny and Edward M. Bassett. The measure was adopted chiefly to stop enormous buildings from preventing light and air from reaching the streets below, and established limits on building at certain heights. Legend has it that the Equitable Building, built in 1916 in Lower Manhattan and occupying an entire city block, was the catalyst for the city’s adoption of the zoning resolution.

1920s — Discriminatory Housing Policies

In 1924, the National Association of Real Estate Boards adopted an ethics code stating, “A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” This remained in the code of ethics until 1950. In 1927, The National Association of Real Estate Boards promoted racially restrictive covenants on deeds to prevent homes from being occupied by African Americans who were not servants of the “rightful owner or occupant.” These policies were accepted as the norm on Long Island.

More Details +

In 1924, the National Association of Real Estate Boards adopted an ethics code stating, “A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” This remained in the code of ethics until 1950. In 1927, The National Association of Real Estate Boards promoted racially restrictive covenants on deeds to prevent homes from being occupied by African Americans who were not servants of the “rightful owner or occupant.” These policies were accepted as the norm on Long Island. In 1926, a KKK rally was held in Mineola and more than 30 Long Island real estate companies took out ads in the rally’s fundraising journal. On Long Island in the 1920s, according to Long Island historian and author, Christopher Verga, the Ku Klux Klan became a dominant force. One out of seven Long Islanders were members of the KKK. In 1923, the Ku Klux Klan burned crosses in a dozen Long Island villages including Freeport, Yaphank, and East Islip.

1924 National Association of Real Estate Boards Ethics Code (PDF)

Newsday “Dividing Lines, Visible and Invisible."

Newsday “A History of Housing Discrimination on Long Island.”

1926 — Euclidian Zoning Upheld

On November 13, 1922, the Euclid, Ohio, Village Council approved a zoning law dividing the village into several districts. The Ambler Realty Company owned 68 acres of land in the village. The ordinance demarcated the use and size of buildings that were permissible in each district. The Ambler Realty Company was limited in the types of buildings it could build on its land. Ambler Realty sued the village, arguing that the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, protection of liberty and property described in the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses. In a 6-3 opinion authored by Justice George Sutherland, however, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that the damages claimed by Ambler Realty were insufficient to overturn what the court judged was an appropriate exercise of the village's power. The decision permitted local governments the power to decide which properties or zones in towns are most suitable for specific uses.

More Details +

The term Euclidean comes from the U.S. Supreme Court decision Euclid vs. Ambler in which the Court upheld the constitutionality of zoning. On November 13, 1922, the Euclid Ohio Village Council approved a zoning law dividing the village into several districts. The Ambler Realty Company owned 68 acres of land in the village. The ordinance demarcated the use and size of buildings that were permissible in each district. Ambler’s land crossed multiple districts, and the company was limited in the types of buildings it could build on its land. Ambler Realty sued the village, arguing that the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protection of liberty and property described in the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses.

A federal district court initially agreed and issued an injunction against enforcement of the ordinance. In a 6-3 opinion authored by Justice George Sutherland, however, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that the damages claimed by Ambler Realty were insufficient to overturn what the court judged was an appropriate exercise of the village's power. The decision permitted local governments the power to decide which properties or zones in towns are most suitable for specific uses.

Euclidean zoning is the separating of land uses by type: residential, commercial, retail, industrial, each into their own zones or areas within a given jurisdiction. While Euclidean zoning is very often associated with the development of suburbia, it's the most common form of zoning code, or a locality’s legal means for controlling the development and uses of land in the United States. Even the country’s largest cities have relied on this form of zoning throughout most of the 20th century and up to the present day.

You can find information on how any parcel of land is zoned on Long Island today, using the Long Island Zoning Atlas: https://www.longislandzoningatlas.org. This is a project of Community Development Long Island, CUNY Graduate Center, Rauch Foundation, and The New York Community Trust.

1929 — Jones Beach opened

Preserving land for public purposes has been an important thread throughout Long Island's history. Jones Beach was conceived and designed by Robert Moses, who was appointed as the first chairman of the Long Island State Parks Commission. It was reported that Moses began sketching ideas for the park in 1923. The establishment of Jones Beach set a precedent for more public parks along Long Island's South Shore that protected the shoreline from commercialization and maintained public access to the shore.

Photo Credit: Tet Arnold von Borsig, 1940, CC BY-SA 4.0

More Details +

Preserving land for public purposes has been an important thread throughout Long Island's history. Jones Beach is the most well-known State Park on Long Island. The park was conceived and designed by Robert Moses, who was appointed as the first chairman of the Long Island State Parks Commission, which was created by legislation that Moses had drafted. It was reported that Moses began sketching ideas for the park in 1923. The 6.5 miles of low barrier beach was added to with dredged sand, stabilized with beach grass, and transformed by amenities such as bathhouses and active recreation facilities into "the people's country club." Jones Beach has become the most visited beach on the East Coast of the U.S. The establishment of Jones Beach set a precedent for more public parks along Long Island's South Shore that protected the shoreline from commercialization and maintained public access to the shore.

Photo Credit: Tet Arnold von Borsig, 1940, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Jones Beach Theater opened in 1952, adding to the attractions at the park.

1933 — Federal Housing Agency

On June 13, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Home Owners’ Loan Act into law and which established the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) to carry out the provisions of the act. The purpose of the law was to deliver emergency aid for home mortgage debt, to refinance mortgages, and to extend relief to the owners struggling under them and who are unable to pay off their debt. During the Great Depression, large-scale unemployment and the impact on wages and income greatly reduced the ability of individual borrowers to meet mortgage payments.

The Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933 rescued hundreds of thousands of homeowners and mortgage lending institutions from loss, and the act and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created a year after the HOLC, completely changed the US mortgage industry. Replacing short-term mortgages and purchase agreements of the 1920s, along with their high interest rates and higher risk, with long-term (mostly 30-year) mortgages at lower rates of interest and backed by the federal government expanded home ownership post-World War II, from under 50% to almost 70% of American families.

More Details +

On June 13, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Home Owners’ Loan Act into law and which established Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) to carry out the provisions of the act. The purpose of the law was to deliver emergency aid for home mortgage debt, to refinance mortgages, and to extend relief to the owners struggling under them and who are unable to pay off their debt. In the 1920s lenders and debtors entered into home mortgage arrangements with faith that the burden could be borne without difficulty, but a huge real estate bubble at the time severely overextended both banks and home buyers. With the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression, large scale unemployment and the impact on wages and income greatly reduced the ability of individual borrowers to meet mortgage payments. At its height, the Great Depression left 24.9% of the nation's workforce, 12,830,000 people unemployed. Wages for workers lucky enough to have kept their jobs fell 42.5% between 1929 and 1933. This quickly led to tax delinquency, mortgage interest default, and eventually to a surge of home foreclosures. By March 1933, millions faced the loss of their homes, lenders faced substantial investment losses, communities began to suffer from an inability to collect property taxes and lost out on badly needed funds, and the construction industry effectively came to a standstill.

New Deal policymakers were aggressive, however, and through the HOLC, prepared loans to assist both financial institutions and Americans overwhelmed by the inability to pay mortgages and property taxes, in addition to home insurance and maintenance. The HOLC acquired distressed and delinquent mortgages by giving lien holders government insured bonds, then made new loans to homeowners that could be paid back over longer periods of time (15 years or more) and at low interest rates (5% or less).

The HOLC was authorized to service and provide loans from June 13, 1933 until June 12, 1936. Over that three-year period, HOLC made over 1 million loans totaling about $3.1 billion, $575 million of which went to individual Americans. The average loan size was $3,039 (over $69,000 in 2022 dollars). The HOLC terminated its operations on April 30, 1951 with a slight profit, defying the expectation that taxpayer money would be lost in the endeavor.

The Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933 proved to be one of the most effective policies coming out of the first 100 days of FDR’s New Deal. Not only did its program rescue hundreds of thousands of homeowners and mortgage lending institutions from loss, the act and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created a year after the HOLC, completely changed the US mortgage industry. Replacing short-term mortgages and purchase agreements of the 1920s, along with their high interest rates and higher risk, with long-term (mostly 30-year) mortgages at lower rates of interest and backed by the federal government. These reforms greatly expanded home ownership post-World War II, from under 50% to almost 70% of American families.

1936 — Nassau County Planning Commission

A revision of the Nassau County Charter, approved by referendum in 1936, created the Nassau County Planning Commission. The Charter gave the Planning Commission the duty of creating a Master Plan for Nassau and approval power over some land subdivisions. This subdivision approval power by the County is unique. In most of New York State, land use decisions are made at the most local level, either town, city, or village.

1936 — Racist Housing Policy

Frederick Babcock and Homer Hoyt are credited with creating the first Underwriting Manual for the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The Manual encouraged racial segregation and pushed the use of racially restrictive covenants to guarantee the most “favorable condition” for neighborhoods. The Manual stated that deed restrictions should include a “prohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended,” and that “inharmonious racial groups” and “incompatible racial elements” would devalue neighborhoods.

1940s and 50s — “Slum Clearance”

Working-class black communities dotted the landscape of Long Island before World War II. Several dated back to the early nineteenth century when freed slaves intermarried with Long Island’s Native Americans. After World War II, as white New Yorkers purchased new Long Island homes, the price of land skyrocketed, and suburban planners began viewing Long Island’s black communities as barriers to continued growth. White residents across the Island were determined to "clean up" neighborhoods in which the blacks lived. In many communities, that meant "clearing" them of African Americans entirely.

Villages like Glen Cove, Long Beach, Freeport, and Rockville Centre toughened local codes, denounced many dilapidated rental unit properties, and began evicting black tenants, many of whom were powerless and not able to find new homes in other areas of the village. Zoning law changes recategorized black residential areas as so-called "slums" for commercial use, which led to the displacement of inexpensive housing by businesses and commercial entities.

More Details +

As in other areas of the country, working-class black communities began to dot the landscape of Long Island prior to World War II. Several dating back to the early nineteenth century when freed slaves intermarried with Long Island’s Native Americans and formed farming communities. In other villages, neighborhoods of black domestic workers were forming near the tracks of the Long Island Railroad, where they were a short ride to and from larger estates long the north and south shores.

After World War II, the quickly expanding suburbs began to burden existing land-use model, including Long Island's racial makeup. The population of Nassau and Suffolk counties doubled between 1950 and 1960. As white New Yorkers purchased new Long Island homes, the price of land skyrocketed, and suburban planners began viewing Long Island’s black communities as barriers to continued growth. Residents in villages and townships across the Island began forming and were determined to "clean up" neighborhoods in which the blacks lived. In many communities that meant "clearing" them of African Americans entirely.

Villages like Glen Cove, Long Beach, Freeport, and Rockville Centre toughened local codes, denounced many dilapidated rental unit properties and began evicting black tenants, many of whom were powerless and not able to find new homes in other areas of the village. Zoning law changes recategorized black residential areas as so-called "slums" for commercial use, which led to the displacement of inexpensive housing by businesses and commercial entities.

State and federal programs proved even more destructive as they provided local governments with the power and assets to rebuild areas categorized as "slums." Numerous suburbs across the country began mirroring what was already happening in urban cities and used the powers of urban renewal to demolish older black communities. On Long Island, Hempstead, Inwood, Rockville Centre, Freeport, Roslyn, Huntington Glen Cove, Long Beach, Manhasset, and Port Washington began suburban renewal efforts targeting black neighborhoods. In these villages, white suburbanites employed the power of the state to redraw the color line and defend privileges associated with class and race. Suburban renewal, like the growth of land-use regulations, had a disproportionate impact on working-class and poor black communities.

An interactive map on the website Mapping Inequality reproduces the redlining maps for American cities created by the FHA Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the 1930s.

Defining Moments: The Civil Rights Movement in North Hempstead [documentary].

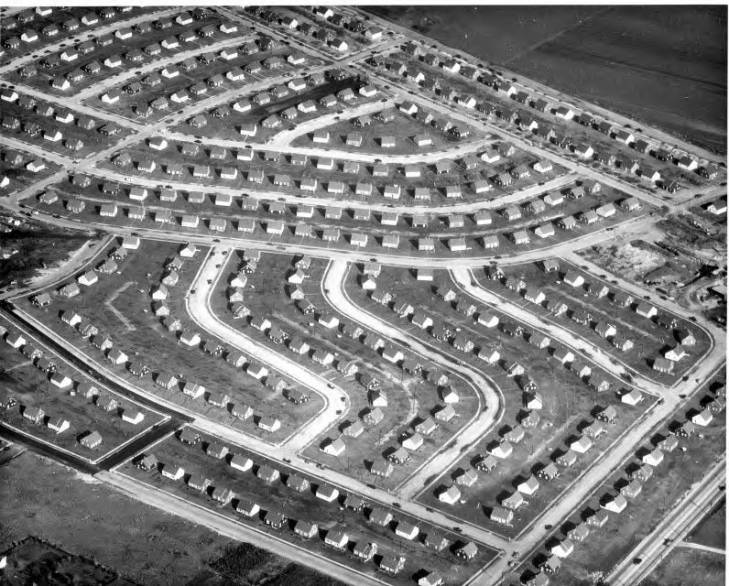

1947 — Levittown

Levittown was planned and constructed from 1947 to 1951. The community was built in response to the demand for housing for returning World War II veterans and is considered the first modern suburb in the country. Levittown’s development gave birth to a new cultural identity of conformity and uniformity.

After WWII, Levitt & Sons, Inc. developed a process to quickly mass-produce homes – more than thirty single-floor homes could be built in a day. Levittown homes cost around $8,000 at the end of the 1940s (approximately $109,000 in 2026 dollars). G.I. Bill benefits reduced the downpayment for veterans to as low as $400 (about $5,450 in 2026). The median price of a Levitt home nearly 8 decades later was $720,000, an increase almost 7 times greater than the rate of inflation. Although all the Levitt homes have been modified, expanded, or rebuilt, and none still exist in their original state for an apples-to-apples comparison, the home equity homeowners could access was crucial in financing those improvements.

The community appeared ideal; soldiers returning from war could live peacefully and without financial hardship. Levittown, however, had a number of stipulations that prohibited certain demographics from buying homes in the area. A clause in the original Levittown covenant stipulated that “the tenant agrees not to permit the premises to be sued or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race.” In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer struck down racially restrictive covenants for violating the 14th Amendment, and the Levittown clause was removed.

More Details +

Levittown was planned and constructed from 1947 to 1951. Named after the firm Levitt & Sons, Inc. founded by Abraham Levitt, the community was built for returning World War II veterans and is considered the first suburb in the country. Levittown’s development gave birth to a new cultural identity of conformity and uniformity, with many women returning from their wartime manufacturing jobs to more traditional domestic roles.

Abraham Levitt and his two sons, William and Alfred, built four communities called “Levittowns” in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Puerto Rico. The Levitt firm had previously constructed homes for upper-middle-class communities across the Island, but after WWII, the Levitts moved to mass-produced homes that could be built quickly – more than thirty one-floor homes could be built in a day. Laborers were paid well, but the Levitts decided not employ union workers for the construction which led to protests and picket lines. The finished home included televisions and modern kitchens. Levittown homes cost around $8,000 at the end of the 1940s, and the G.I. Bill shrunk a home’s cost to just $400, or about $4,500 today. The median price of a Levitt home in today’s market is $720,000.

The community appeared ideal, soldiers returning from war could live peacefully and without financial hardship. Levittown, however, had a number of stipulations that prohibited certain demographics from buying homes in the area. A clause in original Levittown covenant stipulated that “the tenant agrees not to permit the premises to be sued or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race.” In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court case Corrigan v. Buckley ruled that racially restrictive covenants were legally binding documents that made the selling of a house to a black family a void contract. In Levittown, Black veterans were unable to purchase homes, and the Levitts justified the clause by stating that it maintained the value of the properties, since most whites at the time preferred not to live in mixed communities.

Photo: Levittown History Collection. Image for private, educational, and non-commercial use only.

Soon after the opening of Levittown, some white residents fought racism and formed the Committee to End Discrimination in Levittown, to protest the restrictions on the sale of homes in Levittown. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer struck down these racially restrictive covenants for violating the 14th Amendment, and the Levittown clause was removed. Even with the ruling, however, Levittown remained overwhelmingly segregated until the Brown v. Board of Education cases in 1954. Levittown today has a somewhat different demographics, but black residents in the community still comprise an outrageously small minority.

1947–1980s — Sprawl

Post-World War II auto-dependent suburbia began right here on Long Island, starting in Levittown. The new communities evolved as a direct contrast to large cities and sought to respond to perceived urban problems. Suburbs grew to become America's prevailing way of life. Sprawl has been explained in many ways, from development aesthetics to local street patterns. While there is no completely accepted definition of sprawl, there are several common features. Sprawl is a driver of several major challenges facing Long Island. These challenges include air pollution, road congestion, social isolation, and a lack of affordable housing.

More Details +

Post-World War II suburbia began right here on Long Island, starting in Levittown, to address the housing demand of returning military veterans. The new communities evolved as a direct contrast to large cities and sought to respond to their urban problems. From that point suburbs grew as America's prevailing way of life.

Suburbia claims many successes, especially on Long Island, where more than 2.9 million people make their home. Nassau and Suffolk counties have a combined annual economy of $197 billion - bigger than many states and even some countries. Property values are very high, personal incomes run well above the national average, crime is low, and Long Island schools turn out top students. Sprawl is also a driver in several major challenges facing Long Island. These challenges include greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, road congestion, and lack of affordable housing.

Sprawl has been explained in many ways, from development aesthetics to local street patterns. While there is no completely accepted definition of sprawl, there are several common features that allow us to understand its occurrence. Long Island reflects all the characteristics of suburban sprawl, including:

Single family dwellings: The greatest area of land in suburban sprawl is zoned to allow only detached, single family residences. Typically on large lots, potentially up to 5-acre zoning. This low-density encourages builders to construct increasingly large homes, to maximize the selling price. The national average for new homes is approaching nearly 2500 square feet in living space, the average is likely much higher on Long Island.

Dependence on automobiles: Sprawling development patterns create large distances between homes and separate different land uses, forcing residents to rely on automobiles to get from one place to another. Low-density makes public transportation less effective and more costly to provide, locking people into individual auto ownership.

Growth outward from urban centers. Sprawl is also recognized by low-density development expanding away from more densely populated urban centers.

Dispersed patterns of development: An additional, and well-established feature of sprawl is dispersed development, which encourages the expansion of tracts located further out in the landscape over unused areas of land bordering existing developments. Dispersed patterns of development create random and disordered development patterns that can utilize vast amounts of land.

Strip Development: Development in which housing units or commercial properties line roadways extending away from urban centers is an additional feature of sprawling development. Homes built along higher traffic roadways can produce traffic safety dangers, and commercial strips containing fast food chains and/or larger retail chains indulge access by automobile as they are frequently adjoined to sizeable parking lots.

Undefined borders between urban and rural areas: Sprawling home development extending away from urban centers also tends to distort the the borders between urban and rural areas. On Long Island, this type of development pattern has often been the catalyst for efforts to protect open space and agricultural land.

1948 — Racial Covenants declared unconstitutional

On May 3, 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a unanimous 6–0 decision in Shelly v. Kraemer that racial covenants could not be legally enforced, since government action to do so would violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. This rendered racial restrictions in deeds and leases unenforceable.

Levittown racial restriction.

More Details +

In 1945, an African American family named Shelley purchased a home in St. Louis, Missouri. Unaware at the time of purchase, the property had a restrictive covenant in place since 1911. The restrictive covenant prohibited "people of the Negro or Mongolian Race" from inhabiting the property. Louis Kraemer, who lived blocks away, along with other white neighbors sued to prevent the Shelleys from owning the home. The Supreme Court of Missouri said that the covenant was enforceable against the Shelleys because the covenant "ran with the land" and was simply a private agreement between parties, and enforceable against any succeeding owners. The U.S. Supreme Court granted the Shelleys’ case an appeal to consider whether enforcement of racially restrictive covenants violated the Fourteenth Amendment, which stated, in part, that “no state. . . [shall] deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Levittown racial restriction.

On May 3, 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a unanimous 6–0 decision in favor of the Shelleys. The Supreme Court concluded "… restrictive agreements standing alone cannot be regarded as a violation of any rights guaranteed to petitioners by the Fourteenth Amendment so long as the purposes of those agreements are effectuated by voluntary adherence to their terms, it would appear clear that there has been no action by the State and the provisions of the Amendment have not been violated.”

Private parties could accept the terms of a restrictive covenant, but they cannot seek legal enforcement of said covenant, as that would be a state action. Because that kind of action by the state would be discriminatory, the application of a racially restrictive covenant in a state court would then violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

1950s-1970s — “White Flight”

White flight refers to the housing movement of whites leaving urban areas to avoid undesirable amounts of racial integration. On Long Island, a practice called “blockbusting” arose. Real estate agents went door-to-door or blanketed neighborhoods with flyers, warning homeowners that black homebuyers are moving in and declaring that property values will drop. Real estate agents earned commissions on quick home sales as a result of these scare tactics. Between about 1950 and 1970, the practice accelerated the transition of largely white communities like Freeport, Hempstead, Lakeview, Roosevelt, and Uniondale to largely minority communities, and reinforced established segregation practices on Long Island.

More Details +

White flight refers to the housing movement of whites leaving urban areas to avoid undesirable amounts of racial integration.

Between the early 1900s and about 1970, millions of African Americans moved from the south to cities in the Midwest, Northeast, and West during what’s known as the Great Migration.

Upon settling in cities like Chicago, New York, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis, people of color encountered segregation in schools, redlining of neighborhoods, and other forms of discrimination meant to keep neighborhoods and communities from integrating. Throughout the Civil Rights era, as courts enforced integration in schools and ruled against other discrimination efforts, many whites moved out of cities and into developing suburbs.

A history of institutionalized unemployment, abusive policing, and inadequate housing in these northern cities further increased tensions, and riots began to flare up across the country, but especially during the summer of 1967.

In the summer of 1967, more than 150 race-related riots in erupted in cities across the country which were responsible for more than 80 deaths and 17,000 injuries. The summer of unrest led to President Lyndon B. Johnson commissioning a panel of civic leaders to examine the underlying causes of racial unrest in the country. The result was the Kerner Report, a document criticizing white society for fleeing to suburbs, where they barred blacks from employment, housing, and education opportunities. The report’s famous conclusion: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

On Long Island, a practice called “blockbusting” arose. Real estate agents went door-to-door or blanketed neighborhoods with flyers, warning homeowners that black homebuyers are moving in and declaring that property values will drop. Real estate agents earned commissions on quick home sales as a result of these scare tactics. Some agents bought homes at highly reduced prices from frightened white homeowners in order to turn around and sell them to minority buyers at a premium and pocketed the difference.

Between about 1950 and 1970, the practice accelerated the transition of largely white communities like Freeport, Hempstead, Lakeview, Roosevelt, and Uniondale to largely minority communities, and reinforced established segregation practices on Long Island.

1962 — Blockbusting Prosecution

Beginning in the early 60s, cities across the country passed laws intended to stop the practice of blockbusting. State statutes allowed the prosecution of real estate agents who stated that black families were moving into neighboring houses, or who talked about changing the racial makeup of communities. On Long Island, real estate agent Gerald Kutler from Islip Terrace had his real estate license revoked by the State of New York on November 1, 1962. Under a New York State law that prohibited the practice of blockbusting.

More Details +

Beginning in the early 60s, cities across the country passed laws intended to stop the practice of blockbusting. The laws were far-reaching, including restrictions on “For Sale” signs, and bans on real estate marketing and solicitation without a permit. Penalties included real estate license revocation and penalties of $10,000 or a year in jail for first-time offenders.

In addition, states passed wide-ranging laws meant to end blockbusting practices of all kinds. State statutes included prosecution of real estate ages who stated that black families were moving into neighboring houses, or who talked about the changing the racial makeup of communities. The truth couldn’t be used as a defense. Courts upheld these restraints on truthful commercial speech justified by the threat to communities created as a result of blockbusting practices.

On Long Island, real estate agent Gerald Kutler from Islip Terrace had his real estate license revoked by the State of New York on November 1, 1962. Following a series of public hearings convened in New York City approximately two years prior, and based on the testimony of witnesses, the Secretary of State’s Office determined that Kutler’s practices in North Bellport and his colleagues at Captree Realty in Bay Shore, violated Rule 17 of New York’s Real Property Law. The law prohibited the practice of blockbusting, stating,

“No broker or salesman shall solicit the sale, lease or the listing for sale or lease, of residential property on the ground of loss of value due to the present or prospective entry into the neighborhood of a person or persons of another race, religion or ethnic origin; nor shall he distribute material or make statements designed to induce a residential property owner to sell or lease his property due to a change in neighborhood.”

Long Island History Journal: "Blockbusting on Long Island."

Rule 17 was adopted in 1961 by then New York Secretary of State, Caroline K. Simon and made it illegal for real estate agents to instigate the panicked sale of homes, set off racial hysteria, or initiate rapid shifts in the demographics of communities. The Realtor’s Code of Ethics and Real Property Law adopted this addition statewide, its origins, however, took place on Long Island.

The U.S. government got into the act adopting provisions into the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Specifically, § 3604(e) of the Act made it illegal “to induce or attempt to induce any person to sell or rent any dwelling by representations regarding the entry or prospective entry into the neighborhood of a person or persons of a particular race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

Once again, the truth was not a defense. The Fair Housing Act made it illegal to honestly answer a buyer’s question about demographics or racial makeup of a neighborhood. The act specifically stipulated that this behavior was only illegal if it was “for profit.” Talking about race is now illegal, but only for those acting in the capacity of private sector realtors.

1965 — Nassau-Suffolk Regional Planning Board created

The Nassau-Suffolk Regional Planning Board (NSRPB) was established as a cooperative intergovernmental agency by the counties of Nassau and Suffolk to help coordinate planning and address issues faced by both counties, which required regional approaches. The NSRPB was an advisory body with no regulatory power. Lee Koppleman was appointed as the first executive director of the LIRPB and served in that role for forty years. In 2008, the body was reformed as the Long Island Regional Planning Council.

1968 — Fair Housing Act

The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1968, or the Fair Housing Act as it is commonly known was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson and enacted into law on April 11, 1968, two days after the funeral of Martin Luther King. Titles VIII and IX of the act prohibit discrimination by providers of housing, such as landlords, real estate companies, and other entities, such as municipalities, lending institutions, and homeowners' insurance companies, whose discriminatory practices make housing unavailable to persons because of: race, sex, religion, national origin, disability, or familial status.

On Long Island, six days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Levitt and Sons declared that it would adopt a policy of “open housing” as a memorial to Dr. King. It is considered a stunning admission of their past racist policies.

More Details +

The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1968, or the Fair Housing Act as it is commonly known

was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson and enacted into law on April 11, 1968, two days after the funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr. MLK, Jr. was one of the bill’s strongest supporters. He had been at the forefront of the open housing marches in Chicago in the 1960s. President Johnson encouraged Congress to pass the bill and honor the slain civil rights leader before King’s funeral.

Titles VIII and IX of the act prohibits discrimination by providers of housing, such as landlords, real estate companies as well as other entities, such as municipalities, lending institutions, and homeowners insurance companies whose discriminatory practices make housing unavailable to persons because of: race, sex, religion, national origin, disability, or familial status.

The Civil Rights Act initially passed the U.S. House of Representatives in 1966, only to fail in the Senate. President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed for its passage in 1967, but again the bill remained stuck. After the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the subsequent violence that erupted in cities across the United States, President Johnson once again pressed Congress to pass the bill. Debate was intense, but the bill finally passed.

On Long Island, six days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Levitt and Sons declared that it will adopt a policy of “open housing” as a memorial to Dr. King. It is considered a stunning admission of their past racist policies. Despite the passing of time, and laws like the Fair Housing Act, housing discrimination and unequal treatment by Long Island real estate agents persists to this day.

1970 — Racial Intimidation

On September 20, 1970, in an incident that drew nationwide attention, the first African American family to buy property in Massapequa Park discovered the home they were building had been damaged with a sledgehammer and defaced with racist graffiti.

1970 — Nassau Suffolk Comprehensive Development Plan

The Nassau-Suffolk Regional Planning Board (see 1965 above) developed the Nassau-Suffolk Comprehensive Development Plan in 1970. The plan identified preserving open space and agricultural land, providing opportunities for multi-family housing, and improving mass transit options as priorities for the region. The Suffolk County Legislature adopted the plan in 1971. The Nassau County Planning Commission adopted a separate plan in 1971 that was substantially similar to the NSRPB plan, but included more details on Nassau-specific topics. There were claims that the Democratic-majority Nassau Planning Commission acted politically to hamper an incoming Republican county executive before he could appoint new commissioners and create a Republican majority.

New York Times — "Nassau Planners Cause Split on L.I."

1972 — Racial Steering Ruled Illegal

On December 7, 1972, the United States Supreme Court ruled in the case of Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. that the Federal Housing Law gave standing to residents of an apartment complex that housed nearly 8200 residents in San Francisco to sue the owner, Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. The white plaintiffs argued that they had been injured for having lost the social benefits of living in an integrated community; they had missed out on the business and professional advantages which they would have realized had they lived with members of minority groups; and that they had experienced embarrassment and economic harm in social, business, and professional activities from being stigmatized as residents of a ”white ghetto.”

1988 — Long Island Housing Partnership

The Long Island Housing Partnership was established with a mission of providing affordable housing opportunities to those who, without aid, would be unable to secure, or remain in, a decent and safe home through the ordinary operation of the housing market on Long Island. Since the Partnership’s inception in 1988, the Hauppauge-based non-profit and its affiliates have implemented a multitude of programs to foster affordable housing for homebuyers and renters, including: scattered-site developments; smart growth and transit-oriented development; renovation and resale of foreclosures; provision of down payment assistance; employer-assisted housing; and education of prospective homebuyers.

1993 — Pine Barrens Preservation Act

In the 1980s and early 1990s, resistance to spreading sprawl focused on protecting the Long Island Pine Barrens. The Pine Barrens Preservation Act established an innovative transfer of development rights process, which allowed owners of properties in the core protection area to transfer the rights to build on that land to designated receiving zones to allow building at greater density. For more about the Pine Barrens, see the entry in the Environment timeline.

Mid-1990s — Smart Growth

In the late 1980s, tolerance for urban sprawl had reached unsustainable levels in many parts of the United States. By the mid-1990s, the Smart Growth movement began as part of a new urbanist response to sprawl when several large institutions in urban development set out to change the dominant growth paradigm. The effort resulted in the American Planning Association introducing the project “Growing Smart” and releasing the report "Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook: Model Statutes for Planning and the Management of Change in 1997. Around the same time, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Surface Transportation Policy Partnership developed the Smart Growth Toolkit to assist local and state municipalities in creating walkable downtowns and transit-oriented development.

More Details +

In the late 1980s, tolerance for urban sprawl had reached unsustainable levels in many parts of the United States. By the mid-1990s, the Smart Growth movement began as part of a new urbanist response to sprawl when several large institutions in urban development set out to change the dominant growth paradigm. The movement came to be known as Smart Growth after two key events took place. The first, an undertaking of the American Planning Association, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation which was intended to revise local land use controls in an effort to highlight the benefits of denser development patterns. The effort resulted in the American Planning Association introducing the project “Growing Smart” and releasing the report "Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook: Model Statutes for Planning and the Management of Change in 1997. Around the same time, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Surface Transportation Policy Partnership developed the Smart Growth Toolkit to assist local and state municipalities in creating walkable downtowns and transit-oriented development.

In 1996, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency joined with nonprofit and government organizations to create the Smart Growth Network. Partnering organizations of the Network include a range of groups involved in issues that range from the environment and historic preservation to real estate development and transportation.

Further bolstering the movement was the growing academic study and research of the issue of sprawl, and the social and fiscal detriments associated with it. Since its rise, the Smart Growth movement has become very broad. Statements of support for the movement and evidence of Smart Growth initiatives can be found by a variety of organizations and interests, including environmentalists, housing advocates, labor unions, farmers, businesses, public health advocates, and federal agencies.

1997 — Smart Growth on LI

Finding common ground between environmentalists opposed to over-development and developers pushing back against NYMBY (not in my backyard) opposition, a new nonprofit, Vision Long Island, is formed with a mission to educate, advocate, plan, design, and provide technical assistance on Smart Growth projects, transit-oriented development, and downtown revitalization. Vision Long Island has brought best practices of community design together with experts, stakeholders, and decisionmakers to advance quality growth and preservation on Long Island.

1998 — Nassau County Comprehensive Master Plan

The Nassau County Charter, adopted in 1994, in addition to creating a County Legislature (see entry in Local Government timeline), also required the completion of a comprehensive master plan before 1999, and for that plan to be updated at least every five years after its adoption. The Nassau County Comprehensive Master Plan was adopted in 1998, and updated in 2003 and 2008. A draft plan was published in 2010, but has not been officially adopted.

2004–2018 — Long Island Index

For fifteen years, the Long Island Index, a project of the Rauch Foundation, reported on topics of importance to the region. The goal was to provide good, unbiased information to spur action and promote policies to improve the region. Nancy Rauch Douzinas, president of the Rauch Foundation, spearheaded the initiative and served as publisher. Carrie Meek Gallagher served as the initial executive director of the project. A particular issue it brought to greater public attention was "brain drain" — the pace at which young educated people were moving away from the region, due largely to the high cost of housing and lack of housing options. Newsday maintains an archive of Long Island Index reports.

2005 — Housing Bias Continues

Long Island public advocacy organization, ERASE Racism releases the report, Long Island Fair Housing: A State of Inequity, finding failures to address ongoing discrimination and segregation of housing and a lack of enforcement of the Fair Housing Act.

2007 — Copper Beech

Ground broken on the Copper Beech Village townhome complex in the Village of Patchogue, within walking distance of downtown. The 80-unit townhome project reserved 50% of the housing units for qualified affordable households. The revitalization of the Village of Patchogue downtown becomes a model for other LI communities.

2008 — Long Island Workforce Housing Act

The New York State Legislature passed the Long Island Workforce Housing Act for the purpose of making owning a home more affordable for the workforce in Nassau and Suffolk counties. The Act compels developers in Nassau and Suffolk to set aside 10% of their housing units as affordable workforce housing in approved developments with five or more units in exchange for local government approval to exceed existing maximum residential density levels.

More Details +

The New York State Legislature passed the Long Island Workforce Housing Act for the purpose of making owning a home more affordable for the workforce in Nassau and Suffolk counties. Under the Act, the term “affordable workforce housing” is defined as housing for individuals and families at or below 130 percent of the median area income in Nassau and Suffolk.

The Act compels developers in Nassau and Suffolk to set aside 10% of their housing units as affordable workforce housing in approved developments with five or more units in exchange for local government approval to exceed existing maximum residential density levels. Developers can construct the affordable housing units within the approved development or in another development situated in the local government or can instead pay a fee in lieu of building the affordable units. Local government can then use the fee to construct affordable workforce housing, secure land for the purpose of providing affordable housing or repair and renovate buildings for the purpose of offering affordable housing.

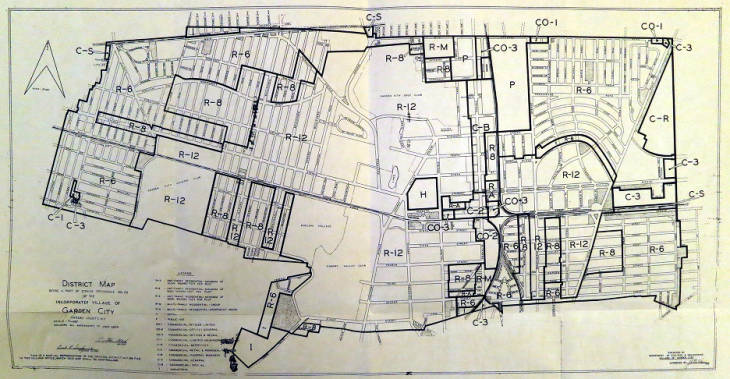

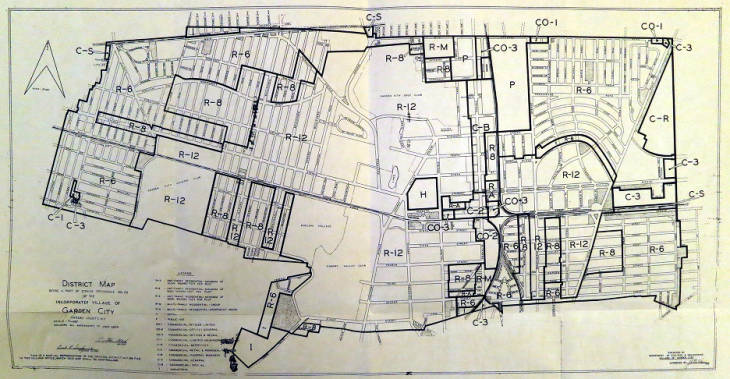

2013 — Garden City Housing Discrimination Suit

Beginning in 2005, New York Communities for Change and Mutual Housing Association of New York filed suit after the Village of Garden City rezoned Nassau County land for the purpose of building townhomes instead of multi-family housing units after residents voiced concerns over the prospect of affordable housing being built in the village. In 2013, a Federal Judge ruled that Garden City "acted with discriminatory intent" in rezoning the property to prevent the construction of affordable housing. In 2018, the Village of Garden City was ordered to pay $5.3 million in the housing discrimination case.

2015 — Suffolk County Comprehensive Master Plan

Suffolk County officially adopted a comprehensive master plan for the first time since the 1971 adoption of the Nassau Suffolk Regional Development plan. (See above.)

Long Island Business News — "Bellone signs Suffolk master plan"

2019 — Racial Steering Continues

A Newsday investigation of housing discrimination on Long Island exposed “widespread separate and unequal treatment of minority potential homebuyers and minority communities,” by real estate firms and brokers across the island. The three-year investigation tested ninety-three real estate agents, secretly recorded 240 hours of meetings, and analyzed 5763 housing listings to uncover their findings.

The Newsday investigation prompted subsequent New York State investigations, which found similar discriminatory practices.

More Details +

A Newsday investigation of housing discrimination on Long Island exposed “widespread separate and unequal treatment of minority potential homebuyers and minority communities,” by real estate firms and brokers across the island. The investigation trained twenty-five undercover testers, tested ninety-three real estate agents, secretly recorded 240 hours of meetings, analyzed 5763 housing listings to uncover their findings over the three-year investigation.

The Newsday investigation was the basis for subsequent New York State investigations. Those investigations allegedly exposed the same kind of wrongful conduct, such as steering potential homebuyers of color (actually trained actors posing as buyers) away from white neighborhoods or holding nonwhite homebuyers to different requirements than white buyers.

Three firms – Keller Williams Greater Nassau in Garden City, Keller Williams Realty Elite in Massapequa, and Laffey Real Estate in Greenvale – agreed to pay a combined $115,000, to settle charges of housing discrimination, without admitting any wrongdoing in the state probe.

Summary and Analysis

Land use decisions of the past have set the stage for the region’s challenges of today. The overwhelming preponderance of detached, single-family residential zoning that prohibited most rentals, coupled with a high level of auto-dependency, has been recognized as a pattern of suburban sprawl that was pioneered on Long Island. This approach deprived communities of housing options, led to segregation and a lack of diversity, and increased the cost of housing. This legacy of land use decisions, makes it difficult both for young people looking to establish themselves and start families, and for older adults who wish to age in place. The dominance of this low-density development pattern also limits opportunities for affordable and multifamily housing, putting pressure on workers, families, and seniors alike. As housing costs continue to rise, many Long Islanders are forced to leave the region in search of more affordable options.

In recent years, examples of successful bottom-up community collaborative planning models are breaking the old patterns and finding success. There is growing recognition that expanding housing choices, through community-engaged zoning reform, transit-oriented development, and support for affordable housing options alongside market-rate homes, is essential to preserving the region’s economic vitality and cultural richness. The land use decisions of the past have shaped today’s challenges. However, recent movements are pointing the way toward a more inclusive and sustainable Long Island.