L.I. How Did We Get Here? Environment

Environment

A Timeline of Environmental Advocacy on Long Island

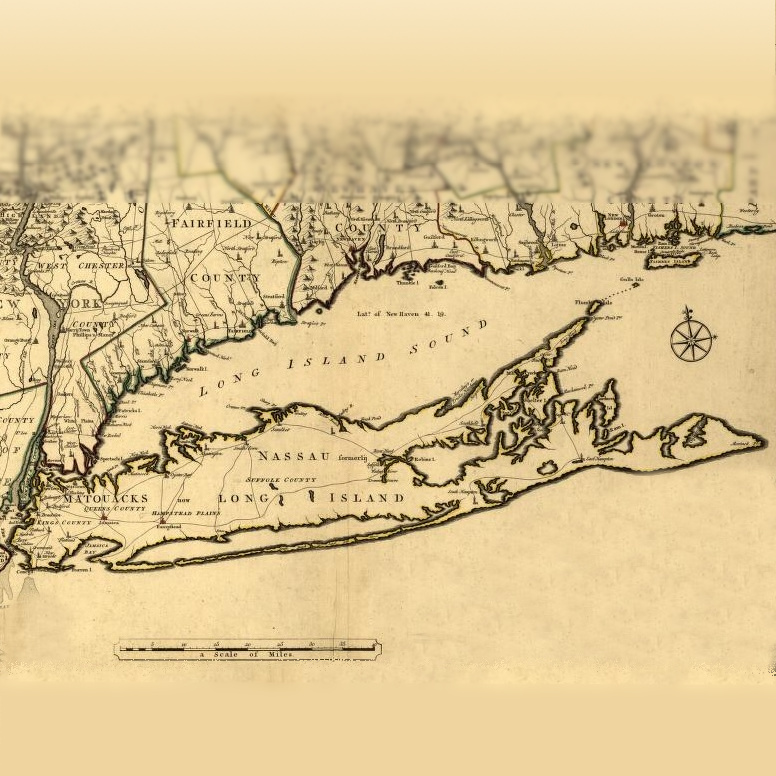

Long Islanders feel a strong connection to our parks, marinas, beaches, and bays. In addition, every Long Island school child learns that the quality of our air is important to our health and that our drinking water comes from the aquifer system beneath our feet. This awareness places the environmental consequences of human actions high in the consciousness of Long Islanders. Due to the Island's environmental sensitivity and because the region became the site of the first heavily auto-dependent suburban sprawl, many environmental issues came to a head here before other regions had to deal with them. Environmental awareness and movements advocating for environmental protection arose on Long Island after the population boomed in the 50s and 60s, and the vulnerability of the region's air quality, drinking and surface waters, and open spaces all became apparent. Long Island voters have consistently supported efforts to set aside funds for open space preservation and drinking water protection, with overwhelming, bipartisan support. Citizen movements on other issues, such as solid waste disposal, recycling, litter, pesticide regulation, renewable energy, and more, were also pioneered on Long Island, with the region providing leadership for New York State, and sometimes even the nation.

Considering our vulnerable environmental resources and the challenges we still face, to successfully implement forward-thinking solutions, it’s worth asking, Long Island: How Did We Get Here?

This 17-minute video presents highlights from the following timeline of environmental advocacy movements on Long Island.

ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY ON LONG ISLAND — TIMELINE OF EVENTS

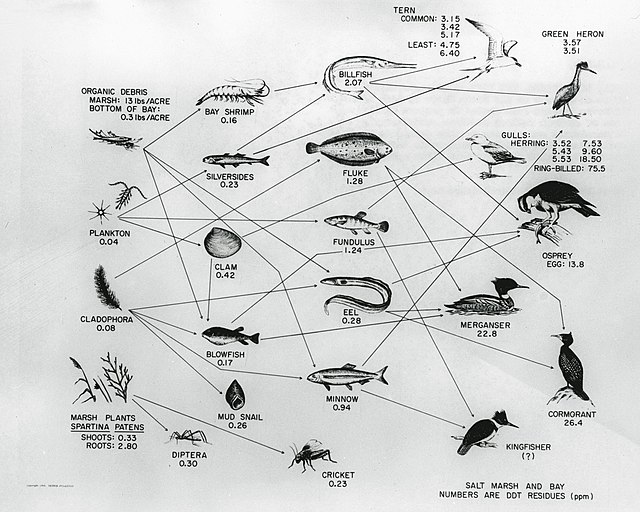

1967 — Environmental Defense Fund Founded

From their living rooms after work in the mid-1960s, a trio of Long Island scientists and avid birders, Art Cooley, Charlie Wurster, and Dennis Puleston came together to discuss and document what they were observing - the decline of the osprey population. These distinguished scientists researching the osprey population decline found that unhatched eggs contained substantial concentrations of the pesticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane). Unprecedented at the time, the scientists joined with a local attorney, Victor Yannacone, who filed a class action lawsuit in the NY State Supreme Court in Riverhead against the Suffolk County Mosquito Control Commission, to stop the use of DDT. The lawsuit was successful in getting an injunction against the use of DDT. In 1967, the group gathered in a conference room at Brookhaven National Laboratory and signed documents of incorporation to form the Environmental Defense Fund.

More Details +

From their living rooms after work in the mid-1960s, a trio of Long Island scientists and avid birders, Art Cooley, Charlie Wurster, and Dennis Puleston came together to discuss and document what they were observing - the decline of the osprey population.

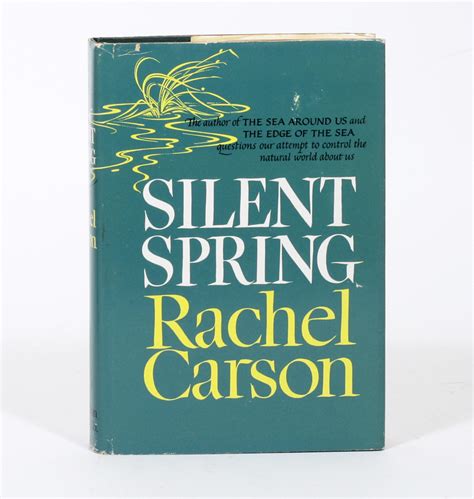

A few years prior in 1962, Rachel Carson’s book, “Silent Spring,” was published. In her book, Carson effectively argued that the pesticide DDT, which had been widely used since WWII, was having a destructive effect on the environment. Specifically, causing the shells of bald eagles and peregrine falcon eggs to thin, weaken, and break, ultimately threatening their survival.

Back on Long Island, this small group of scientists researching the osprey population decline found that unhatched eggs contained substantial concentrations of DDT. They asked the Suffolk County Mosquito Control Commission to stop using the chemical. The commission was unmoved and continued to use DDT, citing its efficacy and cost efficiency.

Unprecedented at the time, the scientists joined with a lawyer and went to the NY State Supreme court in Riverhead and filed a lawsuit on behalf of the environment. They prepared for months and made a convincing case. DDT wasn’t just poisoning bird species, but also crustaceans, while diminishing in value as a mosquito control, as the insects were becoming resistant to it. A few weeks later, the court issued an injunction against the use of DDT by the Mosquito Control Commission. The injunction lasted a year, but the lawsuit was ultimately thrown out. However, in the meantime, Mosquito Control Commission had switched to using a different insecticide and DDT was never sprayed on Long Island again. The scientists had won the case in the court of public opinion.

In 1967, the group along with other environmental activists gathered in a conference room at Brookhaven National Laboratory and signed documents of incorporation to form the Environmental Defense Fund. Their first office was above the Stony Brook Post Office.

Ultimately, the New York State Legislature banned DDT in 1971, and a nationwide ban followed in 1972. Following the national ban, the bald eagle and peregrine falcon were removed from the federal endangered species list, and Long Island osprey populations made a dramatic recovery.

Interview with EDF Founding Trustee Charlie Wurster highlighting the organization’s history.

NY Times article on the passing of EDF founder Dennis Puleston.

LI Press Obituary of Art Cooley.

1970s — Southwest Sewer District Scandal

In 1969 voters in the southwestern portion of Suffolk County voted for establishment of the Southwest Sewer District. The plan soared in price, was hindered by corruption and defrauded taxpayers. Ultimately, turning into a $120-million bid-rigging case and one of the biggest scandals in the history of Suffolk County in which two vendors were convicted and four others paid fines without admitting guilt.

More Details +

In 1969 voters in the southwestern portion of Suffolk County voted for establishment of the Southwest Sewer District. The plan soared in price, was hindered by corruption and defrauded taxpayers. Ultimately, turning into a $120-million bid-rigging case and one of the biggest scandals in the history of Suffolk County in which two vendors were convicted and four others paid fines without admitting guilt.

The scandal took down the administration of County Executive John V. N. Klein of Smithtown. With the scandal central to his campaign, then Islip Town Supervisor Peter F. Cohalan ran against Klein in a Republican primary for county executive and won, then won again in the general election. Cohalan’s campaign slogan called on Republican voters to “Flush Klein.” The scandal effectively ended sewer expansion in Suffolk County for decades. As a result, county officials estimate at least 70 percent of the county relies on cesspools.

1981 NY Times article.

LI Business News article, “Down the Drain.”

Karl Grossman's article touching on the history of the scandal.

1971 — Suffolk Phosphate Ban

The Suffolk Legislature enacted the ban because the slow‐degrading, foam‐producing “surfactants” in detergents were being recycled from the county's cesspools into the shallow water supply on which the county depends for its drinking water. In those days, billows of suds appeared in fresh water and on occasion from water taps in homes.

1970 NY Times article, “Suffolk Accepts Detergents Ban.”

1976 NY Times article.

Associated Press archive video on the ban.

1971 LIFE Magazine article on the ban.

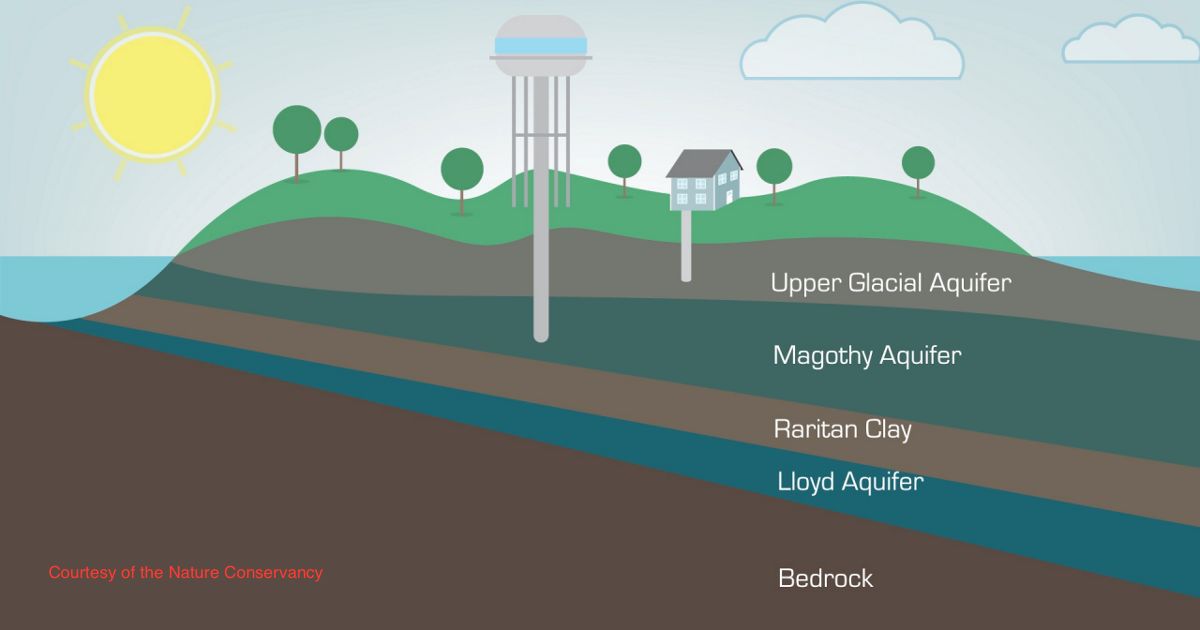

1978 — Federal Sole Source Aquifer Designation

The federal Environmental Protection Agency designated Nassau and Suffolk counties as dependent on a "Sole Source Aquifer" for drinking water. The region was among the first to be named after the regulations for the sole source aquifer program were developed in 1977. Underground aquifers supply all of the drinking water for both counties. The sole source aquifer designation requires the EPA to evaluate any projects in the region that receive federal funding, to ensure they do not endanger groundwater.

Sole Source Aquifers in NY State - US Environmental Protection Agency

1978 — "208 Study" of Long Island's Groundwater Completed

The Nassau-Suffolk Regional Planning Board released the Long Island Comprehensive Waste Treatment Management Plan in July of 1978. The plan was named the “208 Study” because it was developed pursuant to Section 208 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act. The 208 Study was the first attempt at comprehensive water quality management on Long Island. The plan helped create awareness that, unlike most communities that rely upon rivers or reservoirs, Long Island relied upon environmentally vulnerable underwater aquifers for all drinking water needs.

A PDF of the entire study is available here.

More Details +

The Nassau-Suffolk Regional Planning Board released the Long Island Comprehensive Waste Treatment Management Plan in July of 1978. The plan was named the “208 Study” because it was developed pursuant to Section 208 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act. The 208 Study was the first attempt at comprehensive water quality management on Long Island. The plan helped create awareness that, unlike most communities that rely upon rivers or reservoirs, Long Island relied upon environmentally vulnerable underwater aquifers for all drinking water needs.

The 208 study described Long Island’s sole source aquifer system as consisting of three major aquifers: the Upper Glacial aquifer, the Magothy aquifer, and the Lloyd aquifer. Additionally, the study identified eight hydrogeologic zones located across the Island, which created conflicts between the pressure to develop and the need to maintain open space to serve as recharge areas for the aquifers.

A PDF of the entire study is available here.

1981 — Suffolk Bottle Bill

Sponsored by then-Lindenhurst legislator, Patrick Halpin, the bill passed the Suffolk County Legislature by a vote of 12-6 to require 5-cent deposits on soda and beer bottles and cans sold in the county.

At the time, it was regarded as a test of the issue on the state level, which was passed in New York State the following year. The legislation was championed by several Long Island legislators, Robert Sweeney and Thomas DiNapoli in the Assembly, and Kenneth LaValle and James Lack in the Senate. It was signed into law by Governor Hugh Carey. Backing for the bill was generally positioned around the deposits being a way of cleaning up roadways and reducing the amount of waste that municipalities are responsible for disposing.

1981 NY Times article on the bill’s passing the Suffolk Legislature.

1982 NY Times article on the passage of the NY State law.

1981 — Town of Islip Recycling

The Town of Islip becomes the first Long Island Town to establish a recycling program, asking residents to voluntarily separate glass, metal containers, and newspapers. A few years later, the program became mandatory throughout the town, and more Long Island municipalities followed suit.

NYTimes article: "Less Gold in Garbage."

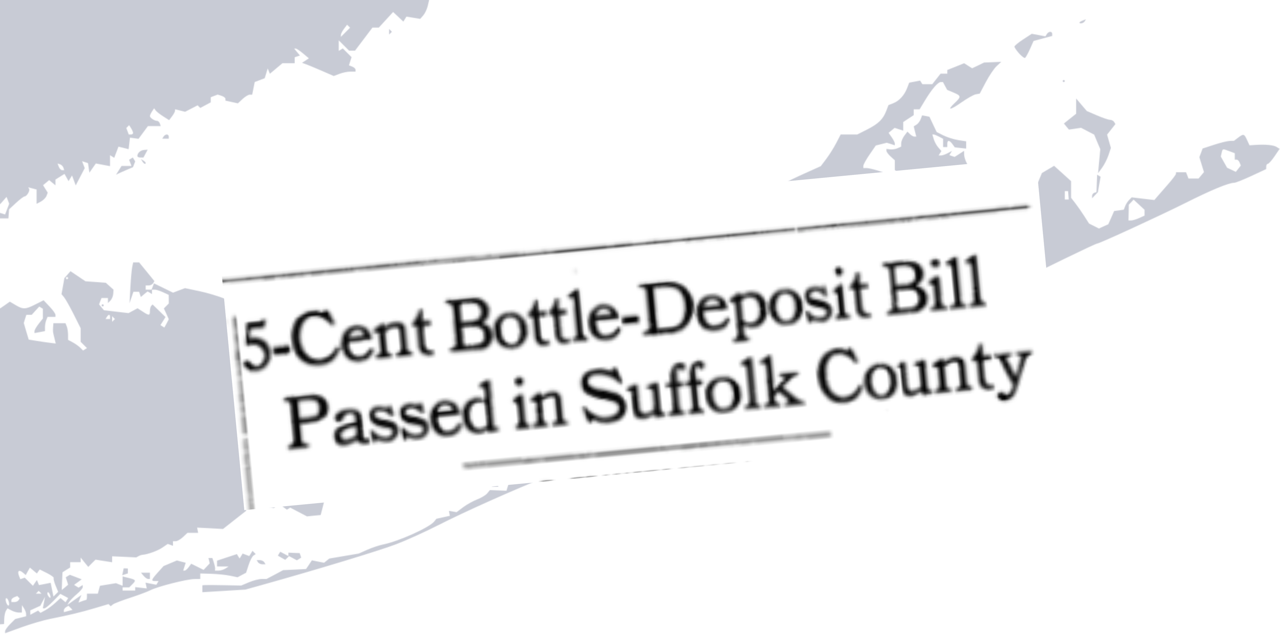

1983 — Long Island Landfill Law

Enacted in 1983, and with the overwhelming support of Long Island elected officials, the Long Island Landfill Law restricted the types of waste that can be placed in landfills to protect drinking water from contamination. The law imposed a moratorium on the use of landfills for garbage disposal over the Island’s aquifer system, which was to be stopped by 1990. Long Island’s supply of fresh drinking water is drawn from an aquifer system that comprises several freshwater zones, or "aquifers." The designation by the Environmental Protection Agency of Long Island as the first sole-source aquifer system in New York State served as the basis for creating the law.

NY Times article: “What the Island’s Landfill Law Specifies”

Local Governments and the Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Business Report from the Office of the State Comptroller.

1985 — Long Island Sound Study Created

The federal EPA and the states of New York and Connecticut form the Long Island Sound Study (LISS). The LISS Management Conference is a partnership of federal and state agencies, user groups, and other organizations united in a mission of improving the health of the Sound. The LISS was included in the inaugural group of estuary programs contained in the EPA's National Estuary Program (NEP) when it was created in 1987.

1985 — Suffolk County Passes Article VII to Protect Long Island’s Drinking Water

In 1985, Suffolk County enacted Article VII of the County Sanitary Code, one of the earliest and strongest local water protection laws in the country. The law regulates discharges of sewage, industrial waste, toxic materials, and stormwater runoff to safeguard the Island’s federally designated sole-source aquifer system. It set rigorous standards for wastewater treatment and land use within deep recharge areas, helping to prevent contamination of the groundwater that supplies all of Long Island’s drinking water. This groundbreaking legislation became a basis for environmental protection policy and a model for similar efforts across the State.

Suffolk County Sanitary Code, Article VII (PDF)

1986 — Suffolk County Voters Approve $60 Million for Open Space Preservation

In 1986, Suffolk County voters overwhelmingly approved a $60 million Open Space Bond Act, one of the first of its kind in the region. The initiative provided funding to purchase and preserve roughly 46,000 acres of farmland, wetlands, and natural habitats, preventing further overdevelopment. This landmark measure reflected Long Islanders’ growing environmental awareness and willingness to invest public funds in protecting the region’s unique landscape and groundwater resources. The program’s success laid the groundwork for future preservation and farmland protection initiatives across the State of New York.

Suffolk County Open Space Acquisition Policy Plan (PDF)

1987 — Suffolk 1/4¢ Sales Tax to Protect Drinking Water

The Suffolk County Drinking Water Protection Program was approved by almost 84% of voters in a referendum to establish Article XII of the Suffolk County Charter. Funded by a 0.25% sales tax, the Drinking Water Protection Program has raised over $1 billion. Most of the money has been used to purchase land and preserve open space in critical water recharge areas, to maintain the quality of drinking water. The program is also designed to reverse groundwater pollution, improve sewage treatment, and stabilize sewer district tax rates. The program has been renewed by voters numerous times since its original inception, by wide majorities.

1987 — Islip Garbage Barge

The barge set sail on March 22 from Islip carrying 3,168 tons of trash headed for a pilot program in Morehead City, North Carolina, to be turned into methane. While in transit, a rumor proliferated that the trash contained hospital waste, syringes, and diapers that contaminated the entire load. Multiple states refused to accept the waste. The nightly news made the story a sensation. It was not until October that it was arranged that the cargo would be incinerated in Brooklyn, and the 430 tons of ash that remained would be dumped at the Islip landfill. The incident sparked national public discussion about waste disposal and was likely a factor in increased recycling rates in the late 1980s and after.

More Details +

Chartered by entrepreneur and owner of the barge, Lowell Harrelson, and Luchese family mob boss, Salvatore Avellino, the barge set sail on March 22 from Islip carrying 3,168 tons of trash headed for a pilot program in Morehead City, North Carolina, to be turned into methane. While in transit, a rumor proliferated that the trash contained hospital waste, syringes, and diapers that contaminated the entire load. The barge was docked at Morehead City until a local WRAL-TV news crew, acting on a tip, flew over the barge by helicopter to investigate. The story broke on the 6 p.m. news on April 1, 1987, and North Carolina officials began their own investigation, resulting in an order refusing to accept the waste. The barge then continued along the coast looking for another place to offload. After an 11-day delay, the barge made its way to its home port in Louisiana, but that state, too, refused to accept the waste. Likewise, Alabama and three other states, the nations of Mexico, Belize, and the Bahamas also rejected the load before the operators abandoned the plan and returned to New York.

The owner of the garbage barge tried to negotiate to dock near Queens, NY, where the load would be carried back to Islip by truck, but Claire Schulman, borough president of Queens at the time, secured a temporary restraining order that forced the waste to stay offshore. The barge stayed off the shores of Brooklyn, decaying until July, when the vessel was granted a federal anchorage in New Jersey. Court hearings ran until October, when it was arranged that the cargo would be incinerated in Brooklyn, and the 430 tons of ash that remained would be dumped at the Islip landfill.

At the time, the incident was widely cited by environmentalists and the media as representative of the solid-waste disposal crisis in the United States and a shortage of landfill space. The incident sparked national public discussion about waste disposal and was likely a factor in increased recycling rates in the late 1980s and after.

NY Times article “Garbage Barge Returns in Search of a Dump”

2017 Newsday project looking back on the 30-year anniversary of the garbage barge.

PBS Retro Report on the garbage barge (video).

1988 — Long Island's First Hazardous Waste Facility Opens in Southold

The Town of Southold opened Long Island’s first household hazardous waste (HHW) facility in 1988, giving residents a safe place to dispose of hazardous materials like paints, solvents, pesticides, and automotive chemicals. Before this initiative, such items were often discarded with regular household trash or down storm drains, risking soil and groundwater contamination. The success of the Southold facility led to the creation of similar programs across the Island, establishing Long Island as a state leader in safe waste management and recycling efforts.

Town of Southold – Hazardous Waste Program

1989 — “The War of the Woods”

In the late 1980s, real estate development, including strip malls and housing developments of suburban sprawl was responsible for Long Island losing vast acres of its valued woodland Pine Barrens at the rate of nearly 5,000 acres a year. The ecosystem that once covered 250,000 acres had declined to an estimated 125,000 acres. At the time, 234 development projects were proposed in the remaining Pine Barrens area. The Long Island Pine Barrens Society, which had been founded in 1977, by John Cryan, Robert McGrath, and John Turner for the purpose of protecting the Pine Barrens and educating the public about the vital ecosystem, took action. On November 21, 1989, the Pine Barrens Society filed the largest environmental lawsuit in the history of New York State, asking the State Supreme Court to require a collective environmental assessment of all the projects in this critical region under the State Environmental Quality Review Act.

More Details +

In the late 1980s, real estate development, including strip malls and housing developments of suburban sprawl was responsible for Long Island losing vast acres of its valued woodland Pine Barrens at the rate of nearly 5,000 acres a year. The ecosystem that once covered 250,000 acres had declined to an estimated 125,000 acres. At the time, 234 development projects were proposed in the remaining Pine Barrens area. The Long Island Pine Barrens Society, founded in 1977 by John Cryan, Robert McGrath, and John Turner. to increase public understanding of the significance of the Pine Barrens found itself in a historic effort to stop development before the Pine Barrens ceased to be a viable ecosystem.

Photo by Sandra Richard CC BY-NC 2.0

On November 21, 1989, the Pine Barrens Society filed the largest environmental lawsuit in the history of New York State, asking the State Supreme Court to require a collective environmental assessment of all the projects in this critical region under the State Environmental Quality Review Act.

In 1992, the Court of Appeals (the highest court in New York State) ruled against the Pine Barrens Society. However, in the decsions, the Court noted, "[A]n exhaustive and thorough approach to evaluating projects affecting this region is unquestionably desirable and, indeed, may well be essential to its preservation." However, "We in the judiciary are not free to piece together statutes and regulations that were never meant to address a problem of this magnitude... the solution must be devised by the Legislature." This, along with the public awareness created by the lawsuit and campaigns by the Pine Barrens Society and other environmental organizations put pressure on the New York State Legislature to act.

The Society quickly gained a reputation as determined fighters for drinking water protection and open space preservation. The founders enlisted communications professional and community education expert, Richard Amper, as their first professional staff person. They educated him on everything about the Pine Barrens and tasked him with developing and executing a campaign to save the Pine Barrens.

During the campaign, the Society emerged as one of the most effective environmental groups in the state and achieved protection of some 55,000 acres of Pine Barrens through landmark legislation, the Pine Barrens Protection Act. Richard Amper and the Pine Barrens Society won several awards for their efforts and received regional and national recognition for the conservation campaign.

Pine Barrens Society co-founder, John Turner, on the significance of the Pine Barrens (video).

1990s — Long Island Breast Cancer Activism Connects Health and the Environment

In the mid-1980s, studies showed that women on Long Island were dying from breast cancer at higher rates than those elsewhere in New York State or the nation. An initial study by the New York State Health Department pointed to demographic and lifestyle factors. These findings were disputed by breast cancer activists who argued that the research ignored or downplayed environmental causes. Their pushback mobilized a new wave of grassroots activism across Nassau and Suffolk counties.

Local leaders, including: Karen Miller of the Huntington Breast Cancer Action Coalition and Prevention Is the Cure; Lorraine Pace and Virginia Regnante of the West Islip Breast Cancer Coalition; Geri Barish of 1 in 9: The Long Island Breast Cancer Action Coalition; Laura Weinberg of the Great Neck Breast Cancer Coalition; and Elsa Ford of the Brentwood Bayshore Breast Cancer Coalition, became central voices demanding accountability.

Founded on November 27, 1990, 1 in 9: The Long Island Breast Cancer Action Coalition was named to highlight the fact that one in nine women in the U.S. were expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetimes. The coalition and its partners called for comprehensive federal research to examine whether pesticide use, industrial runoff, or drinking water contamination were contributing to the island’s unusually high cancer rates.

Their advocacy led to the creation of the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project in 1993, a federally funded effort to explore environmental links to breast cancer. However, the epidemiological study of cancer is inherently complex and difficult. The study did not establish any clear environmental factors in the rate of breast cancer on Long Island.

Working with environmental organizations, activists also pushed for stronger pesticide regulation and cleaner water. 1 in 9 supported a compromise that helped secure passage of the New York State Pesticide Reporting Law, which limited access to the data to a small number of approved researchers and aggregated the data in a way that prevented the public from getting a detailed picture of which pesticides were applied and where. A number of environmental groups, including Albany-based Environmental Advocates, cautioned against this compromise because it failed the goals of a public right to know.

Advocacy also extended to consumer protection. Karen Miller partnered with Suffolk County Legislator Steve Stern on legislation banning bisphenol-A (BPA) in baby bottles and sippy cups in 2009, making Suffolk County an early leader in restricting the chemical. In 2010, New York State adopted the same ban, demonstrating how local breast cancer activism helped shape statewide policy. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned BPA in baby bottles in 2012.

BPA is a synthetic chemical used in plastics and food packaging, and research has shown that it can disrupt the endocrine system, raising concerns about its possible role in hormone-related cancers.

Through their persistence, Long Island’s breast cancer coalitions reframed breast cancer as not only a medical crisis but also an environmental and public health issue. Their work reshaped national conversations on prevention, environmental justice, and women’s health while pushing governments at every level to take environmental exposures seriously.

New York Times article on the Pesticide Reporting Law (subscription required)

New York Times article of the Suffolk County BPA ban (subscription required)

New York State Senate press release on the state BPA ban

HBCAC/Prevention is the Cure history

Historical perspective on Long Island breast cancer activism

West Islip Breast Cancer Coalition website

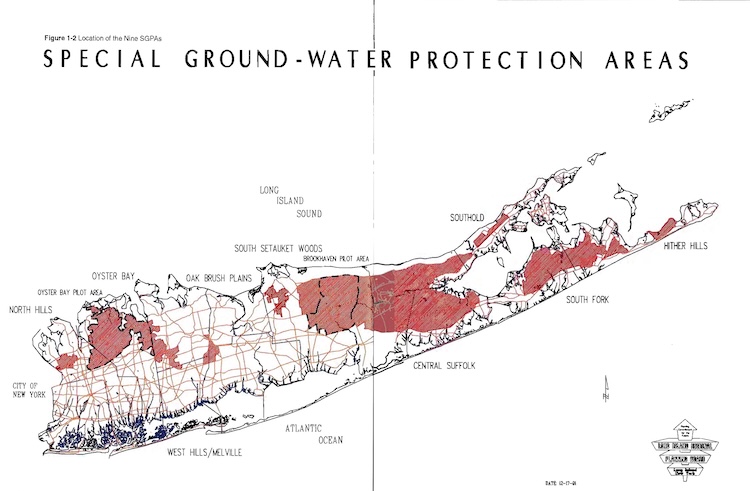

1992 — Special Groundwater Protection Area Plan released

New York State enacted the Special Groundwater Protection Areas (SGPA) Law in 1987 (Article 55 of New York's Environmental Conservation Law). The law outlined the framework for designating SGPAs within federally identified Sole Source Aquifer regions, such as Long Island, and named the Long Island Regional Planning Board (previously Nassau Suffolk Regional Planning Board) as the planning entity for SGPAs in Nassau and Suffolk counties. The LIRPB released The Long Island Comprehensive Special Groundwater Protection Area Plan in 1992. Nine SGPAs were identified on Long Island as important for maintaining adequate volumes of high-quality groundwater.

More Details +

New York State enacted the Special Groundwater Protection Areas (SGPA) Law in 1987 (Article 55 of New York's Environmental Conservation Law). The law outlined the framework for designating SGPAs within federally identified Sole Source Aquifer regions, such as Long Island, and named the Long Island Regional Planning Board (previously Nassau Suffolk Regional Planning Board) as the planning entity for SGPAs in Nassau and Suffolk counties. The LIRPB released The Long Island Comprehensive Special Groundwater Protection Area Plan in 1992. Nine SGPAs were identified on Long Island as important for maintaining adequate volumes of high-quality groundwater. These SGPAs are crucial for recharging the deep aquifers that provide drinking water; therefore, policies that aim to protect water quality by controlling or restricting development in SGPAs are considered reasonable restrictions to achieve drinking water protection goals. Under New York State’s environmental quality review laws, SGPAs meet the designation of Critical Environmental Areas (CEAs). This designation signifies their unique ecological, geological, or hydrological sensitivity and requires lead agencies to provide a hard look during SEQRA review regarding the potential impact of a proposed development.

LI Special Groundwater Protection Plan (PDF) - Long Island Regional Planning Board

1992 —Long Island Cases Inspire New York’s Anti-SLAPP Law

In the late 1980s, several Long Island residents found themselves hit with multimillion-dollar lawsuits after protesting local development projects.

In Wantagh, resident Betty Blake organized candlelight vigils and neighborhood protests against a developer, Terra Homes, that was replacing single-family homes and cutting down old trees in an area that local residents called "Wantagh Woods." When she and her neighbors distributed leaflets critical of the builder, the company sued Blake for $6.6 million. Justice John S. Lockman dismissed the case, calling it “an American microcosm” that illustrated both the rights of builders and the right of citizens to protest.

These and similar "strategic lawsuits against public participation" (SLAPPs) resulted in statewide attention and mobilized activists and lawmakers. The cases highlighted how developers could use the courts to intimidate residents who spoke out on zoning, land use, and environmental issues. Public backlash led to the passage of New York’s first anti-SLAPP law in 1992, aimed at protecting citizens from retaliatory lawsuits meant to silence their civic engagement.

Since then, 38 states have enacted anti-SLAPP laws. New York's law was the first, and is considered the gold standard.

NY Times article on SLAPP (subscription required):

Center for Health, Environment & Justice Fact Pack about Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation

1992 — Toxic Fairways Report

In 1990, the NYS Attorney General's Office surveyed 107 public and private golf courses on Long Island. 52 golf courses completed the survey. The responding golf courses used a total of approximately 200,000 pounds of dry and almost 9,000 gallons of liquid pesticides. In all, 192 different pesticides and 50,000 pounds of active ingredient were applied on those 52 golf courses. The report on the survey, released by Attorney General Robert Abrams in 1991, cited studies involving golf course superintendents finding elevated levels of cancer risks. It also criticized lax regulations and deficient worker training and raised concerns for people living near golf courses, which use significantly more pesticides than are used on farms.

The report was later updated in 1995 by New York State Attorney General Koppel.

1992 — Peconic Estuary

Peconic Estuary accepted into the National Estuary Program as one of 28 “Estuaries of National Significance.”

1993 — South Shore Estuary Reserve Act

The New York State legislature passed the South Shore Estuary Reserve Act. This created a partnership of State agencies, local governments, and other stakeholders to develop and implement a management plan for the system of bays, tidal marshes, and tributaries along Long Island's South Shore.

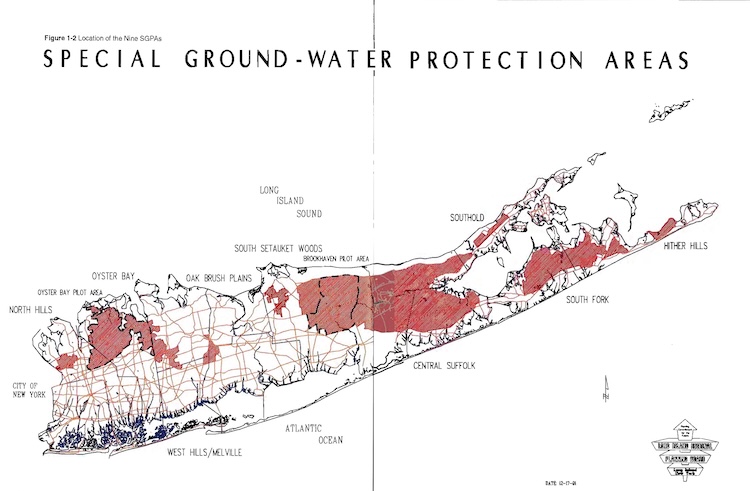

1993 — Long Island Pine Barrens Protection Act

An unprecedented compromise between environmentalists, business leaders, and government representatives produced the Long Island Pine Barrens Protection Act.

A 1992 ruling by the Court of Appeals in the case of Pine Barrens v. Planning Board highlighted the need for unified planning in the critical environmental area, but decided it could not be imposed by the court and required legislation. The Long Island Pine Barrens Society, led by Richard Amper, and other environmental groups negotiated with builders and state Legislators to hammer out details of a law to protect the most sensitive areas of habitat and groundwater recharge, while recognizing the property rights of landowners, and allowing for appropriate economic development.

The Act, passed by the State Legislature and signed into law by then-governor Mario Cuomo, protected the Pine Barrens forever. It established a five-member Central Pine Barrens Joint Planning & Policy Commission to oversee the development and implementation of a Comprehensive Management Plan (CMP). The new law delineated two major regions within the 100,000-acre area – a 53,000-acre Core Preservation Area where no new development is permitted and a 47,000-acre Compatible Growth Area where limited, environmentally compatible development is allowed. The Act incorporated the concept of Transfer of Development Rights. Property owners prohibited from building in the Core Preservation Area could sell their development rights to owners of property in receiving areas, allowing them to build more densely.

Governor Mario Cuomo signing the Long Island Pine Barrens Protection Act

The story of the Pine Barrens Protection Act, as told by the Pine Barrens Society.

NPR article and audio about the fight to save the Pine Barrens:

1994 — HealthyPlanet’s Annual Turkey-Free Thanksgiving Dinner and Lecture Series

In 1994, HealthyPlanet launched its first Turkey-Free Thanksgiving Dinner/Lecture Series, which quickly evolved into one of Long Island’s largest and longest-running community Thanksgiving events (1994 to 2019). The annual celebration was the highlight of HealthyPlanet’s monthly, fully plant-based potluck and lecture series, featuring nationally recognized speakers, authors, scientists, and physicians addressing topics such as health, the environment, climate change, and the suffering of animals.

Designed as both an educational and participatory experience, the events modeled a new, eco-friendly, compassionate holiday tradition that offered the abundance of a Thanksgiving meal without the turkey. The potluck format encouraged attendees to prepare and share whole-food, plant-based dishes, helping participants develop practical skills for long-term dietary and lifestyle change.

Over its 25-year run, the series hosted more than 200 events and drew nearly 20,000 participants, making it a major public education effort on Long Island. Entirely volunteer-driven, it built a diverse community centered on sustainability and wellness while highlighting other nonprofit groups working towards positive change. For its final eight years, the series was hosted by The Sustainability Institute at Molloy University, which provided an ideal venue for this vibrant community tradition.

HealthyPlanet website

1995 —Nassau County Pesticide Phase-Out Executive Order

Nassau County Executive Thomas Gulotta, while flanked by breast cancer activists and environmentalists, signed an executive order directing the phase-out of the use of pesticides on county parks. When he signed the executive order to phase out pesticides on county property, he noted that Nassau was taking the "national lead" in recognizing the potential environmental links to the high cancer rates on Long Island. Describing his shift towards a “pesticide-free” policy for turf maintenance, he said, "If there is any doubt, we must err on the side of caution. The health and safety of our residents, particularly our children, must come before the aesthetic of a perfectly green lawn.” Meanwhile Geri Barish of 1 in 9, demanded that government act to reduce exposures to toxic substances in the environment.

Daily News article.

1996 — Nassau County Neighbor Notification Law

One of the first pieces of legislation introduced in the new Nassau County Legislature was a law to require written prior notification to neighbors of properties where pesticides were to be sprayed. The legislation was sponsored by Peter Schmitt, the Legislature's first Presiding Officer. The law was championed by the environmental organization, the Long Island Neighborhood Network, in response to several incidents of residents being exposed to pesticides that were being sprayed on neighboring properties.

The law was struck down in the courts, on the grounds that the County is preempted from regulating pesticide application, which is regulated by State law and the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. The decision intensified calls for a State-wide law, which was enacted and took effect in 2001 (see below).

NY Daily News article about the court decision.

1996 – Creation of Homecoming Farm and the Growth of Community Supported Agriculture on Long Island

In 1996, the Sisters of St. Dominic in Amityville founded Sophia Garden, later renamed Homecoming Farm, as part of the growing Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) movement. The farm became one of Long Island’s oldest certified organic CSA projects, providing fresh produce to members, donating harvests to hunger relief, and advancing sustainable land use. Preservation efforts, including the Nassau County Environmental Bond Act that protected Meyer’s Farm in Woodbury and Grossman’s Farm in Malverne, reflected a wider regional shift toward organic farming and farmland conservation. In 2023, the Sisters transferred the development rights to Homecoming Farm to the Peconic Land Trust, ensuring that the land would remain undeveloped and be used exclusively for open space, agricultural, and associated educational purposes.

Bond Act supporting Meyer’s Farm, Grossman’s Farm article

Homecoming Farm video

More Details +

In 1996, the Sisters of St. Dominic in Amityville launched Sophia Garden, later renamed Homecoming Farm, as part of the Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) movement. Led by Sister Jeanne Clark, the project modeled a sustainable way of living centered on organic farming and became one of Long Island’s oldest certified organic CSA farms. Rooted in the belief that caring for the Earth means caring for one another, Homecoming Farm not only supplied fresh vegetables to CSA members but also donated a portion of its harvest to local hunger relief efforts.

Homecoming Farm’s mission reflected a larger shift on Long Island toward organic produce, sustainable land use, and community-based agriculture. The CSA model involves a direct relationship between local farms and consumers, where members pay upfront for a season's worth of fresh, seasonal, and often organic produce. At the same time, preservation efforts underscored the importance of protecting the island’s limited farmland. The Nassau County Environmental Bond Act helped secure properties such as Meyer’s Farm in Woodbury and Grossman’s Farm in Malverne, ensuring that some of the county’s few remaining farms were protected for future generations. Together, these developments highlight how Long Island contributed to advancing organic produce, community-based farming, and even inspiring home gardeners to reduce reliance on pesticides.

In 2023, the Sisters ensured that the land would continue its mission of environmental stewardship by transferring Homecoming Farm to the Peconic Land Trust, cementing its role in Long Island’s organic farming history and its contribution to the region’s environmental and food justice movements.

1998 — Peconic Bay Region Community Protection Fund

On election day, 1998, voters in the five East End Town (East Hampton, Riverhead, Shelter Island, South Hampton, Southold) approved referenda to establish a 2% tax on the sale of real estate to fund the preservation of open space, farmland, and community character. Key environmental advocacy groups that supported the Community Protection Fund included the Group for the South Fork (now Group for the East End), the Nature Conservancy, the North Fork Environmental Council, and the LI Pine Barrens Society. In 2006, voters extended the program. It was again extended by another referendum in 2016, which also expanded it to allow 20% of the fund to be used for water quality improvement projects. In 2022, the tax was increased to 2.5% by voters in all the towns other than Riverhead.

History of the Community Protection Fund

1999 — Suffolk County Pesticide Phase-Out Law

The legislative intent of Suffolk County Local Law No. 33-1999, introduced by Legislator David Bishop, was to "phase out the use of pesticides by the County for many pest control purposes, and to adopt a pest control policy that substantially relies on non-chemical pest control strategies."

Supporters of the measure cited the "precautionary principle" and the potential links between pesticide exposure and public health issues, specifically the high rates of breast cancer on Long Island. The bill's passage represented a significant shift in County policy, moving toward Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and organic land maintenance on the County’s publicly-owned facilities and phasing out the use of chemical pesticides.

New York Times article on the passage of the law.

This webpage from the Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County explains the implementation of the law.

More Details +

Key Details of the Legislation

Phase-Out: The ban specifically targeted pesticides in the EPA's Toxicity Category I and those classified as possible carcinogens—first. Designed as a phase out, the use of pesticides on public properties and in County buildings. To be fully implemented by July 1, 2003, pesticide use declined each year, working towards elimination.

Scope: This applied to properties owned or leased by the County, which included parks and county-owned golf courses.

Implementation: The law also established the Pesticide Community Advisory Committee (CAC) to oversee the transition and review potential emergency waivers or exemptions.

The Law mandated a transition to Integrated Pest Management (IPM), which involves: Using biological and natural controls; prioritizing non-chemical maintenance practices; allowing only "lower toxicity" substances.

1999–2012 – Organic Turf and Tree Show and Organic Landscaper Listing

From 1999 to 2012, the Long Island Neighborhood Network held an annual Organic Turf and Tree Show that promoted local businesses offering less toxic landscaping services and provided professionals with the latest practices for maintaining healthy turf without chemical pesticides. The event featured vendor displays from leading organic suppliers and workshops that offered DEC continuing education credits.

Building on the effort, the Neighborhood Network created an annual Organic Landscaper List, identifying Long Island professionals trained in organic methods, tested for knowledge, and operating under standards that prohibited harmful products and practices. The organization also conducted an annual Long Island Lawn and Garden Center survey to identify where Long Islanders could purchase alternatives to toxic pesticides, making it easier for homeowners to transition to safer lawn care products.

During this same period, Grassroots Environmental Education, founded by Patricia and Dave Wood, amplified public awareness about pesticide risks through community outreach and education campaigns, including a Long Island Rail Road poster campaign that urged residents to consider safer alternatives to lawn chemicals. Together, these initiatives helped shift local attitudes toward organic land care and demonstrated how community organizations could influence pest management practices while protecting Long Island’s sole-source aquifer system.

2003 Organic Store Survey Press Release

2004 5th Annual Trade Show Program

2015 Long Island Organic Landscaper List

Grassroots Environmental Education website

2001 — New York State Neighbor Notification Law

On August 21, 2000, then New York State Governor George Pataki signed the Neighbor Notification Law, capping a nine-year bipartisan effort. Assemblyman Thomas DiNapoli (who later became NY State Comptroller) was the lead sponsor. The law, which was conceived of and advocated for by Long Islanders, requires 48-hour prior written notification to adjacent neighbors of properties where pesticides are to be sprayed. The historic, first-in-the-nation statute paved the way for additional environmental regulations and similar laws in other states.

Governor George Pataki signing the Neighbor Notification Law. Bill authors and primary sponsors State Senator Carl Marcelino (left) and Assemblyman Thomas Dinapoli (right) stand next to him. Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos stands directly behind the Governor. Neal Lewis, then executive director of the Long Island Neighborhood Network, stands behind and right of Senator Skelos.

More Details +

On August 21, 2000, then New York State Governor George Pataki signed the Neighbor Notification Law, capping a nine-year campaign that started on Long Island. The law requires 48-hour prior written notification to adjacent neighbors of properties before pesticides are to be sprayed. The effort began when the environmental organization, Long Island Neighborhood Network, received a call from a member who proceeded to tell staff attorney Neal Lewis about a pesticide exposure incident her infant was subjected to on a summer day in 1992. The Neighborhood Network proceeded to propose legislation to protect families from unnecessary pesticide exposure to then Long Island Assemblyman Thomas DiNapoli, who championed the reform early in the 1993 legislative session. He drafted and became the prime sponsor of the Prior Neighbor Notification of Pesticide Spraying bill. Later, Senator Carl Marcellino boosted the effort when, upon his election to the State Senate in 1995 became the bill’s prime sponsor in the Senate in his first term. This meant the effort had "same as legislation" in both chambers with bipartisan sponsorship. For nine years, Long Island Neighborhood Network organized a door-to-door and telephone campaign across Long Island to educate the public, distribute hundreds of thousands of brochures, and generate thousands of phone calls and letters from constituents to their elected officials calling for the passage of the bill. The bill was strongly opposed by the pesticide industry and upstate farmers, despite not restricting agricultural pesticide use.

However, demand for prior notice of pesticide spraying mounted. This notice of pesticide spraying would allow families to take common-sense precautions, such as closing windows, removing children's toys from the lawn, and keeping pets indoors. Many complaints came from pet owners,because dogs or cats in a backyard can easily be exposed to spraying on neighboring properties.

The proposed legislation proved popular at a time when people were demanding a 'right to know' about toxins in the environment, as evidenced by the work of breast cancer activists. The law requires that the written notice to neighbors include the name of the pesticide being sprayed, because when exposures happen, knowing the chemical is necessary for taking appropriate action. The name of the company doing the spraying is also included on the notice. Providing the public with information also help to promote awareness of the widespread use of pesticides and rasied questions about their necessity.

The nine-year legislative logjam was finally broken by a compromise that introduced language in the state legislation to allow individual counties to ‘opt in’ to the law’s protections. This allowed urban and suburban counties to require notice, while allowing legislators in rural counties to block implementation. The various advocates supporting the law all agreed to the compromise. Nassau and Suffolk counties immediately opted in. The law is now enforced in: Albany County; Erie County; Monroe County; Nassau County; Rockland County; Suffolk County; Tompkins County; Ulster County; Westchester County; and New York City.

What started as an environmental protection effort had grown into an environmental health rights movement. Combined with the efforts of a broad coalition of homeowners, environmentalists, and breast cancer action organizations took the movement statewide. Upon becoming a top environmental priority, Albany-based environmental organizations suggested adding school notices to the bill, which further enhanced its already strong public support. Once implemented, this first-in-the-nation law brought about significant changes in pesticide applicators’ practices. To avoid notice requirements, many tree-spraying companies began using horticultural oils and soaps, which were exempt from the law, significantly reducing spraying of chemical pesticides on trees.

Governor George Pataki signing the Neighbor Notification Law. Bill authors and primary sponsors State Senator Carl Marcelino (left) and Assemblyman Thomas Dinapoli (right) stand next to him. Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos stands directly behind the Governor. Neal Lewis, then executive director of the Long Island Neighborhood Network stands behind and right of Senator Skelos.

NYS Dept. of Health’s Neighbor Notification Law Fact Sheet

New York Times article, “Legislature to Vote on Pesticide Measure”

New York Times article “Pesticide Applicators Must Notify Neighbors”

NYS Dept. of Education Neighbor Notification Law Reminder

2001 — Nassau County establishes the Open Space and Parks Advisory Committee (OSPAC)

The creation of the Open Space and Parks Advisory Committee (OSPAC) was unanimously approved by the Legislature in June of 2001 for the purpose of making recommendations to the Nassau County Planning Commission on the acquisition, preservation, protection, restoration or enhancement of open space, parks, and areas of recreational, cultural, archeological or historical significance. A prime responsibility of OSPAC is to review County-owned parcels for their open space and recreational value before they can be sold by the County.

Press Release — Nassau Legislator Judy Jacobs

2002 —Suffolk County Golf Course Plans Blocked by Pesticide Litigation

Suffolk County’s plans for five (5) new golf courses ran into growing concerns over the heavy use of chemicals on golf courses (see the Toxic Fairways report). By applying the precautionary principle, people began to consider the use of toxic pesticides for turf management, where the benefits are primarily aesthetic, as not being worth the risks. Then, a court ruling recognized the need for new golf courses to follow rigorous evaluations during the environmental review process, making conventional golf course construction difficult to get through to approval. County Executive Robert Gaffney withdrew his support for five new golf courses after a lawsuit was filed challenging compliance with environmental laws and recognizing that those plans were running against the drive towards phasing out heavy reliance upon chemical pesticides for turf management.

More Details +

The Suffolk County Golf Course Initiative involved a plan by County Executive Robert Gaffney to utilize a request for proposals (RFP) process to identify private companies that would operate under contract with the County to design, build, and manage five (5) new golf courses on County land that would be open to the public. The environmental group Long Island Neighborhood Network filed an Article 78 in State Supreme Court in Hauppauge (Lewis v. Gaffney), arguing that the RFP process violated SEQRA and did an end-run around the Suffolk County Pesticide Phase Out Lawby allowing private golf companies to avoid complying with the same rules that county workers were required to follow on county-run parks and golf courses. The Long Island Neighborhood Network worked with a coalition of environmentalists and breast cancer activists that called themselves the Organic Golf coalition. The premise behind the name was to draw an analogy with organic produce by establishing rules for golf course maintenance that prohibit most pesticides and instead relied upon course design features, water management practices, horticultural soaps, oils, and some bio-pesticides.

The Suffolk County lawsuit got a boost when the appellate division second department issued a ruling blocking construction of a golf course in Rockland County for a failure to conduct an environmental impact statement (EIS) to evaluate risks associated with the use of pesticides over a drinking water supply. Matter of S.P.A.C.E. v. Hurley, 291 A.D.2d 563 (N.Y. App. Div. 2002). Link to the decision @ Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide: https://elaw.org/resource/us-space-v-hurley-291-ad2d-563-739-nys2d-164-ny-app-div-2002

This case involved a proposed municipal golf course (295-acre) in the Town of Stony Point. The organization S.P.A.C.E. (Stony Point Action Committee for the Environment) brought the Article 78 proceeding to challenge the Town Board’s "negative declaration" under SEQRA. The lawsuit asserted that the town—which was both the lead agency responsible for SEQRA compliance and also the entity that was seeking to get the project approved and had budgeted on the revenue that the new golf course would generate—failed to take a “hard look” at the concern that pesticides applied on a golf course built directly over an aquifer that serves as the primary drinking water source for residents might present a thread of drinking water contamination.

The Appellate Division overturned the lower court decision and found that the Town's vote to approve a negative declaration (Neg Dec) and therefore not require an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), was "a circumvention of SEQRA`s open and comprehensive review process.” The court required that a full EIS be prepared, holding that “even an Expanded Full EAF cannot legitimately serve as a substitute for an EIS and the attendant analysis and public discussion entailed in a proper SEQRA review.”

The Appellate Division ruling established a precedent that there is a “low threshold” for determining when an EIS is required, and had the practical effect that new golf courses were unlikely to get approved without following a rigorous EIS process and presenting a plan to mitigate or eliminate pesticide use that presents a risk of contaminating drinking water. Although the case was brought in Rockland County, it had connections to the Organic Golf coalition on Long Island, as the Long Island Neighborhood Network joined the case as co-petitioners. Several months after the decision in S.P.A.C.E. v. Hurley, Suffolk County announced that it would no longer pursue the plan for five new courses as part of the Suffolk County Golf Course Initiative, which the incoming newly elected County Executive Steve Levy indicated he had no interest in pursuing for economic reasons.

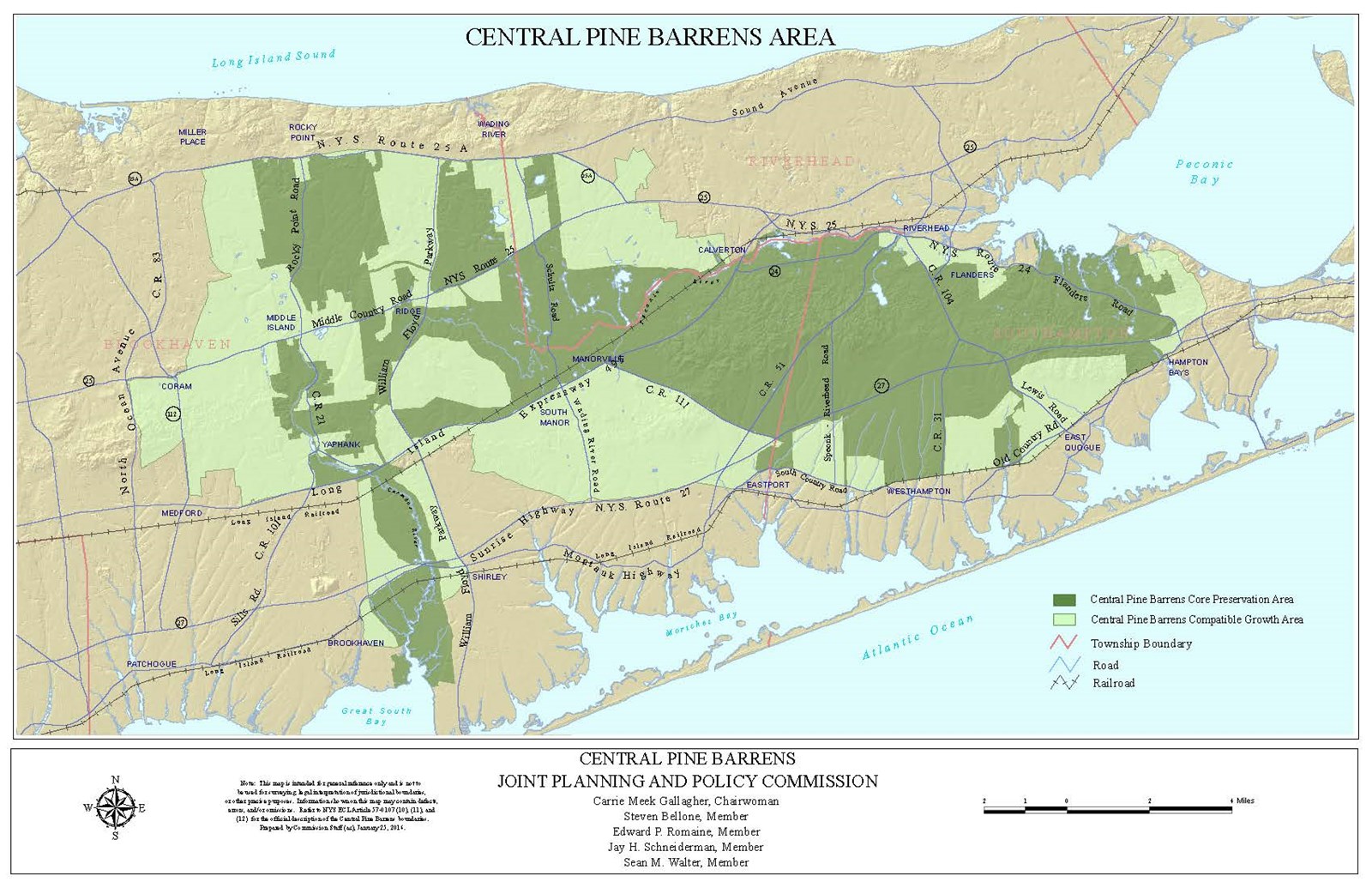

2004 & 2006 — Nassau Environmental Program Bond Acts

The Nassau County Legislature unanimously voted in 2004 to place a referendum on the ballot on bonding a $50 million Environmental Program. The measure was signed by County Executive Thomas Suozzi, and in November of that year, Nassau County voters overwhelmingly approved (77% voting yes) issuing bonds to fund an environmental program. Further funding of $100 million in bonds was approved in 2006, again by 77%. The program had four goals: 1) preserving open space, 2) improving parks, 3) implementing stormwater treatment systems, and 4) remediating brownfields.

Environmental Bond Act Land Acquisitions - Nassau County

2005 — Energy Star Homes Code

At the urging of the Long Island Neighborhood Network, Babylon and Brookhaven adopted requirements for new home construction to meet ENERGY STAR Homes standards. Eventually, all but two of Long Island’s thirteen towns followed suit.

Front row: Brookhaven Town Council members Kathleen Walsh, Kevin McCarrick, Tim Mazzi, and Connie Kepert, Brookhaven Supervisor Brian Foley, Neal Lewis, and Babylon Supervisor Steve Bellone visit a model ENERGY STAR Home in August 2006, shortly after Brookhaven passed the mandatory ENERGY STAR Homes code.

The Long Island Power Authority provided each town or municipality that passed a similar law a $25,000 grant to help train inspectors to assess new home construction. These codes were among the most stringent home-building energy efficiency standards in the nation

More Details +

The ENERGY STAR Certified Homes project was introduced by the EPA in 1995. The voluntary program was intended to help buyers of new homes identify and choose houses that are significantly more energy-efficient than standard construction. A vital part of the program is an inspection and rating by an independent, third-party Home Energy Rating System (HERS) rater, accredited by the Residential Energy Services Network (RESNET), a nationwide, not-for-profit organization founded by the National Association of State Energy Officials and Energy Rated Homes of America.

The proposal to adopt local codes and make the national standard for ENERGY STAR Labeled Homes a mandatory code requirement rather than just a voluntary, incentive-driven program, was introduced and developed in 2005 at meetings of the L.I. Clean Energy Leadership Task Force. The idea was borrowed from a similar local law in the Town of Greenburgh, New York.

The concept was further debated at two meetings of the Long Island Association’s (LIA) Environment/Energy Subcommittee, which helped to identify concerns of the Long Island builders.

A primary concern of residential developers was that there were not enough certified HERS raters on Long Island, which would lead to bottlenecks in getting new homes approved. They proposed altering the propose law to require homes meet the ENERGY STAR standard, but not require the HERS rating.

The laws supporters pointed to studies that showed poor rates of compliance with existing codes, and insisted that third-party verification was essential. The only compromise they would accept was a phase-in period, to allow time for builders and raters to be trained to meet the requirements.

This compromise lead to the proposal gaining the support of the Long Island Builds Institute (LIBI). As a result, LIBI became one of the first builders trade groups in the country to support higher efficiency standards. The LIA board of directors formally endorsed the policy, and directly encouraged all towns to adopt the standard. Newsday printed a number of editorials urging towns to adopt the measure. There was broad support from environmental groups such as the Sierra Club and the Group for the East End.

Long Island Power Authority provided each town or municipality passing a similar law a $25,000 grant to help train inspectors to assess new home construction.

In 2006, the towns of Babylon and Brookhaven adopted the codes, with the sponsorship of Brookhaven Town Councilwoman Connie Kepert and Supervisor Brian Foley and Babylon Town Supervisor Steve Bellone. Eventually, 11 of the 13 towns on Long Island adopted similar codes.

In 2006, the EPA updated the ENERGY STAR Homes standard, making it considerably more stringent. Rather than have their building codes tied to a program that could change without their input, the Long Island towns that had adopted the ENERGY STAR standard as a code amended their local laws to require new homes to achieve specific HERS indexes instead. When the code was no longer tied to the ENERGY STAR Homes program, the Town of Southampton adopted a tiered system, which required larger homes to meet higher energy efficiency, making it one of the most stringent residential construction energy codes in the nation

The program has proved that establishing better efficiency standards can result in substantial emissions reduction, with little or no expense, while creating long-term savings for homeowners, and advancing “Green Economy” jobs.

Sustainability Institute Green Paper.

NYSERDA letter to the EPA 2005: https://www.energystar.gov/ia/partners/bldrs_lenders_raters/downloads/NYSERDA.pdf

ENERGY STAR Homebuilding Standards.

2006 — Sebonack Golf Club Opens with Environmental Stewardship

Aware that golf course proposals had generated opposition and, in some cases, litigation, before the proposed developers of the Sebonack Golf Club went public with their proposal, they reached out to the Organic Golf coalition, seeking to find common ground by promising to design and build a golf course to the highest environmental standards. Today, the Sebonack Golf Club has the strongest environmental bona fides of any golf course in the Northeast.

More Details +

Aware that golf course proposals had generated opposition and, in some cases, litigation, before the proposed developers of the Sebonack Golf Club went public with their proposal, they reached out to the Organic Golf coalition, seeking to find common ground by promising to design and build a golf course to the highest environmental standards. Today, the Sebonack Golf Club has the strongest environmental bona fides of any golf course in the Northeast. The course has been recognized for its significant environmental leadership, particularly through its sustainable design and management. Showcasing best practices, including reducing impact on local water bodies by utilizing rain runoff and treated effluent for irrigation, with systems to ensure cleaner water leaves the property than enters. While maintaining native areas, pollinator habitats, monarch butterfly zones, bluebird boxes, and buffer zones around water, and restricting the use of inputs. According to Audubon International, “Sebonack serves as a prime example of how golf courses can integrate with nature, protecting resources while providing high-quality golf experiences.”

Owner and developer Michal Pascucci, along with project manager Mark Hissey, proved true to their word and lived up to their commitment to sustainable design and operating with environmental stewardship as the central tenet of their turf management credo. Throughout the multi-year environmental review and Southampton Town’s famously rigorous zoning process, Pascucci and Hissey worked closely with Robert (Bob) Deluca and the Group for the South Fork to develop a sustainable golf course management plan and closely monitor environmental compliance. DeLuca described the agreement with Sebonack Golf as a “landmark compromise,” and “the most comprehensive environmental management plan ever attached to a Long Island golf course.” The golf course was certified as an Audubon International Signature Sanctuary, and, in 2008, it received the MGC/MetLife Club Environmental Leaders in Golf Award.

2009 — LI Unified Solar Permit

In the early 2000s, the solar installation permitting process on Long Island necessitated a different set of policies for every town and village, which created confusion, added extra costs, and was responsible for installation delays. During a meeting of the Long Island Clean Energy Leadership Task Force, an initiative administered by the Sustainability Institute at Molloy University, the idea of a unified, streamlined permit process was advanced. Under the direction of the Suffolk County Planning Commission Chair, David Calone, a committee was formed, which included representatives from the Nassau and Suffolk County Planning Commissions, industry professionals, the Long Island Power Authority, and several municipalities. The Committee endeavored to establish a permitting process that would maintain thorough safety measures and quality control, but also fast-track approvals for standard solar rooftop installations.

The permit has been adopted by most Long Island Towns and some villages, and became the model for the unified solar permit promoted to municipalities Statewide by New York State.

More Details +

In the early 2000s, the solar installation permitting process on Long Island necessitated a different set of policies for every town and village, which created confusion, added extra costs, and was responsible for installation delays. During a meeting of the Long Island Clean Energy Leadership Task Force, an initiative administered by the Sustainability Institute at Molloy University, David Calone, chair of the Suffolk County Planning Commission presented the idea of a unified, streamlined permit process was advanced. Under the direction of the Planning Commission, a committee was formed, which included representatives from the Nassau and Suffolk County Planning Commissions, industry professionals, the Long Island Power Authority, and several municipalities. The Committee endeavored to establish a permitting process that could maintain thorough safety measures and quality control, but also be achieved quickly.

The committee proposed an accelerated and standardized process for residential solar power systems. The new Solar Energy System Fast Track Permit Application process allows municipalities to meet the governing requirements, while reducing the time and money associated with approving solar installation permits. An additional aspect of the application includes waiving the need for a survey of the entire property or other information not relevant to the installation. To encourage municipalities to adopt the initiative, the Long Island Power Authority provides incentives to each Long Island town and to each of the first ten villages where the standard is adopted. It has been adopted by most Long Island towns and some villages.

Long Island Unified Solar Permit Initiative Solar Energy System Fast Track Permit Application.

ARTICLE: “A Model for Expediting Solar Permits: Long Island Unified Solar Permit Initiative”

2010 — Safe School Grounds Law

On May 10, 2010 then governor, David Patterson signed the Safe School Grounds bill into law. The law also prohibits pesticides used for lawn care on school grounds, playgrounds, turf, athletic and playing fields. In the nine previous legislative sessions professional lobbyists in Albany extensively representing the chemical industry successfully ensured that the bill died in the Senate. The requirements of the law are administered by the State Education Department for schools and by the Office of Children and Family Services for day care centers

More Details +

On May 10, 2010 then governor, David Patterson signed the Safe School Grounds bill into law. In the nine previous legislative sessions professional lobbyists in Albany extensively representing the chemical industry successfully ensured that the bill died in the Senate. For years prior to and after the passage of the Neighborhood Notification Law in 2001, environmental organization, Long Island Neighborhood Network had been building momentum in demanding safer pesticide use in schools. In 1995, the Neighborhood Network published and distributed the report, “Pesticides and Children: Avoiding the Risks,” which was one of the first highly publicized educational efforts bringing attention to the special risks pesticides posed to children. In 1998, the Neighborhood Network established the Pesticide Alternatives Project, which focused on the availability of alternative and organic lawn and garden maintenance products. In 2002, the Neighborhood Network organized the Toxic-Free Schools Project empowering parents to demand changes in school pest control policies and offering help to schools in designing and implementing pest control plans that do not rely on toxic, synthetic pesticides. At the time it was estimated that over 10 million pounds of pesticides are applied on Long Island every year. A 2000 study by the state attorney general’s office determined that 87 percent of schools in New York use pesticides, with almost 65 percent using pesticides outdoors.

In the 2010 NY State Legislative Session, the bill was sponsored by two Long Island elected officials, Senator Brian X. Foley in the Senate, and Steven Englebright in the Assembly. The bill addressed a growing body of research and evidence that children are especially susceptible to pesticide exposure. The bill gained widespread statewide attention and was passed in both houses of the Legislature. The bill was supported by the Healthy Schools Network, Grassroots Environmental Education, and Environemntal Advocates of New York. The law bans almost all uses of chemical pesticides on the grounds of schools and day care centers and protects children from unnecessary exposure to toxic pesticides. The law also prohibits pesticides used for lawn care on school grounds, playgrounds, turf, athletic and playing fields. The law does not apply to pesticides used in a health emergency, as determined by the county health department or school board, or to protect children from an imminent threat of biting, stinging and venomous pests. The requirements and guidelines of the law are administered by the State Education Department for schools and by the Office of Children and Family Services for child care centers.

Former NYS Senator Brian Foley’s press release on the law’s passage:

Dept. of Environmental Conservation guidance (PDF) on the law: https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/materials_minerals_pdf/guidancech85.pdf

American Academy of Pediatrics statement on pesticide exposure in children:

2010 – The Sustainability Institute at Molloy University’s Sustainable Living Film Series

Beginning in 2010, the Sustainability Institute at Molloy University hosted the Sustainable Living Film Series, screening documentaries on environmental and ethical issues. The series drew up to 200 attendees at each screening, partnered with local nonprofits, and built connections between Long Island’s social change community and the public.

More Details +

Launched in 2010, the Sustainability Institute at Molloy University’s Sustainable Living Film Series was a free public program that screened documentaries focused on environmental protection, animal and environmental ethics, and sustainability. Each screening partnered with a nonprofit organization, creating opportunities for networking and collaboration among Long Island’s social change community. With up to 200 attendees at each event, the series fostered unity between local organizations and the broader public while also broadening Molloy’s circle of friends. Target audiences included teachers, Molloy faculty and students, nonprofit professionals, and community members, but all were welcome to attend.

Over the course of its run, twenty-five films were screened, drawing attention to critical issues and building connections that extended well beyond the campus. The series not only provided education and dialogue on key sustainability challenges but also enhanced the university’s reputation as a convener of community engagement around social and environmental issues.

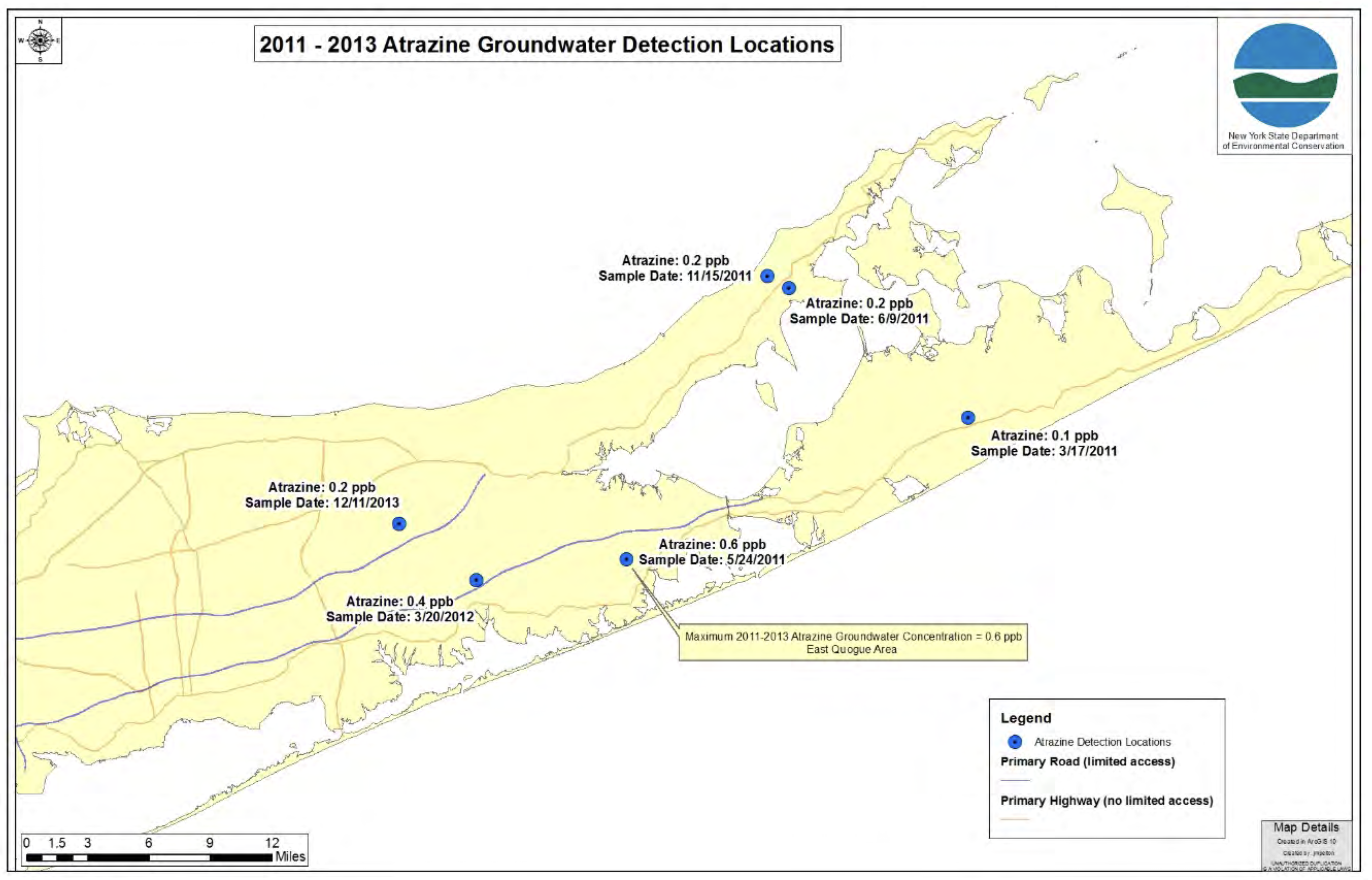

2013 — Long Island Phases Out the Toxic Pesticide Atrazine

After many years of public pressure and growing evidence that atrazine, an herbicide linked to groundwater contamination and health risks, was polluting Long Island’s aquifers, its manufacturers agreed in 2013 to stop selling the product in the region. Environmentalists, scientists, and local governments had long campaigned for the ban, citing repeated findings of the pesticide in drinking water wells. The decision to remove atrazine marked a significant victory for environmental and public health organizations, highlighting Long Island’s leadership in chemical regulation and groundwater protection.

Riverhead News Review article - “Weed-killing chemical yanked from sale on Long Island”

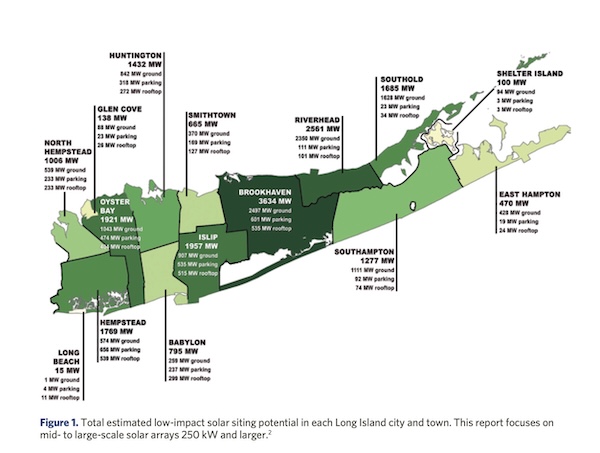

2016 — “Green for Green” controversy: solar power vs open space

Proposals for several utility-scale solar arrays on eastern Long Island raised concerns about the loss of open space. Open space advocates and neighbors of proposed solar farms strongly opposed the cutting of trees for large solar projects, claiming it was losing one ‘green,’ open space, for another ‘green,’ renewable energy. Some of the projects were approved and completed, while others were killed.

Read a Newsday article about the controversy around a proposed solar farm (subscription required).

2017 — Suffolk County Plastic Bag Fee

The debate about how to approach plastic bags and the environmental impact they have has been a hot topic on Long Island for several years. On Jan. 1, 2017, the legislature passed a bill to require supermarkets, pharmacies, clothing stores, and other retailers to charge 5 cents for every non-reusable paper or plastic shopping bag, with some exceptions. One of the primary environmental groups supporting the legislation was Citizens Campaign for the Environment, led by executive director Adrienne Esposito. Later reporting on the law indicated that between 2017 and 2018, there was a 42% decrease in plastic bags that cleanup volunteers found littering Suffolk shorelines.

More Details +

Debate about how to approach plastic bags and the environmental impact they have had been a hot topic on Long Island for several years. A Suffolk county bill was proposed in 2016 to ban plastic bags altogether, but it failed to gain necessary support in the county legislature. Instead, on Jan. 1, 2017 the legislature required stores to charge 5 cents for every non-reusable paper or plastic shopping bag, with some exceptions. The county law, passed by a 13-4 vote, requires supermarkets, pharmacies, clothing stores, and other retailers to charge customers 5 cents for each single-use plastic or paper bag they use to carry purchases.

Environmental advocates supporting the bill cited data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that indicates that between 500 billion and 1 trillion plastic bags are consumed worldwide every year, and that Americans use more than 10 billion paper bags each year. In addition, an estimated 14 million trees are cut down each year to make paper bags. One of the primary environmental groups supporting the legislation was Citizens Campaign for the Environment, led by executive director, Adrienne Esposito. The Suffolk law aimed to boost reusable bag use and reduce the number of single-use plastic bags polluting waterways and threatening marine life. Following passage of the bill a one-year effectiveness report in 2019 by Suffolk County’s Department of Health Services indicated that use of single-use plastic bags was down 81.7% and single-use paper bags was down 78.8% compared with 2017. The report also showed that in November and December 2017 and in the first two-month of 2018, that use of reusable bags or no bags increased from 27.8% to 60.1%. Furthermore, the reporting indicated that between 2017 and 2018, there was a 42% decrease, to 1,552, in plastic bags that cleanup volunteers found littering Suffolk shorelines.

Newsday article: “Suffolk plastic bag use down by 1.1 billion, report says”

Suffolk County Department of Health Services One-year Effectiveness Report (PDF)

2020 — New York State Plastic Bag Ban

Plastic bag use poses significant environmental damage when bags end up as litter on the side of roadways, in trees, and in waterways where they pose an imminent threat to marine life. After several municipalities around the state passed their own single-use plastic bag prohibitions, New York State became the third state in the country, behind California and Hawaii, to pass a bag ban of its own. The law affects all non-exempt plastic bags from distribution by anyone required to collect New York State sales tax. Examples of an exemptions are bags used by a pharmacy to carry prescription drugs, take-out food, and produce bags for bulk items such as fruits and vegetables.

Patch article on the plastic bag ban.

More Details +

Plastic bag use poses significant environmental damage when bags end up as litter on the side of roadways, in trees, and in waterways where they pose an imminent threat to marine life. After several municipalities around the state passed their own single-use plastic bag prohibitions, New York State became the third state in the country, behind California and Hawaii, to pass a bag ban of its own. In New York, where some 23 billion plastic bags are used each year, the Bag Waste Reduction Law went into effect on March 1, 2020. It was not immediately enforced, however, a result of a lawsuit brought before the NYS Supreme Court. In the complaint, the defendants called the rule vague and unconstitutional, and alleged that it directly conflicted with another state recycling law.

On Aug. 20, 2020, a State Supreme Court judge ruled against the defendants, upholding the ban on plastic bags and giving the State Department of Environmental Conservation the green light to begin enforcing it on October 19, 2020. After the effective date, however, the COVID-19 pandemic further delayed rollout and enforcement. Studies have shown that use of single-use plastics increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, as more people opted for takeout food delivery, and local enforcement agencies have looked the other way as small businesses struggled during the state shutdown.

The law affects all plastic bags (except those exempt) from distribution by anyone required to collect New York State sales tax. For sales that are tax exempt, plastic carry out bags are still not allowed to be distributed by anyone required to collect New York State sales tax (unless it is an exempt bag). The law also affects anyone required to collect New York State sales tax, bag manufacturers and consumers. Examples of an exempt bag are bags used by a pharmacy to carry prescription drugs and produce bags for bulk items such as fruits and vegetables.

From the beginning, an important element of the state law has been to encourage consumers to bring their own bags. The law is not intended to replace single-use plastic bags with single-use paper bags, the law was intended for people to bring reusable bags, and not intended to put the burden on the store owners. That remains a point of contention as businesses report that they are bearing the cost burden of replacing plastic with paper, and that they want regulators to allow them to use up their remaining stock of plastic bags before switching. They also note that many customers stop by their establishments on their way home from work or appointments and haven’t necessarily planned in advance to pick up grocery items. Environmentalists have their own complaints with regulators, largely that enforcement remains slow some two years after the law’s passage, and that plastic bag use continues to be ubiquitous as a result.

Citizens Campaign for the Environment was a leading advocate for the law. CCE excutive director Adrienne Esposito said, "On March 1, after working for 10 years to ban plastic bags we will finally be free of these harmful unnecessary pollutants... It is all of our responsibility to fight plastic pollution, and this is one small thing everyone can do to help. We just have to get on the plastic bag ban wagon."

About 79 percent of plastic waste ends up in landfills, rivers and oceans where it can remain for hundreds of years, according to the United Nations. Even when the larger plastic products degrade, they remain in oceans in a smaller form, known as microplastics, which are easily ingested by fish and wildlife.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Fact Sheet on the law.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation information for retailers and manufacturers:

State Supreme Court’s full decision (PDF).

https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/materials_minerals_pdf/polypakvsny.pdf

2021 —Bay Park Sewage Treatment Plant Conveyance Project Breaks Ground